The 20 Coolest Macro Creatures in the Ocean

In the big, blue ocean, oftentimes it’s the little things that capture a diver’s fascination — here are 20 of our favorite wacky, weird and wonderful macro critters.

Andrey SidorovA nudibranch sits on rope sponge near the 500-foot Umbria wreck in the Red Sea.

Networking types are forever saying that the more people you meet, the smaller your world becomes. Divers know a similar truth: The more hours you log underwater, the smaller your world becomes. You feel the pull of fascination from ever tinier wonders, from lettuce sea slugs to pygmy seahorses. You train your eye accordingly. Photographers, especially, are quick to embrace the macro, and it pays off in myriad ways.

Says Alex Mustard, an underwater photo pro and marine biologist, “New species are nearly always found by underwater photographers because they’re finding things in these smaller size ranges.”

His advice to all divers: “Go slow — the more time you spend looking, the more of these amazing creatures you will see.”

1. Frogfish

Bruce ShaferThe striated frogfish

It happens to every diver: The day you learn of this odd-shaped swimmer, obsession takes hold. And rightly so. Few creatures found as close to home for East Coast divers as the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico and even the Atlantic as far north as New Jersey offer that needle-in-a-haystack hunting challenge — and thus a huge pat on the back.

And yet, their behavior rivals drying paint.

“Their whole mode of resistance is to not respond to movement,” says Ted Pietsch, a University of Washington ichthyologist specializing in frogfish. “They don’t do very much except sit and wiggle that bait, holding the body completely still.”

No movement, no detection. An exception is the striated frogfish (above), which prefers open flats, such as eelgrass beds. It’s more active than the longlure, the species best known among divers.

As for the longlure’s statuelike stillness, Pietsch is quick to mention the upshot.

“This is why divers can so easily approach.”

Divers can cozy up to witness Pietsch’s favorite detail: the lure.

“In every species, the little lure is slightly different, mimicking small organisms, from copepods to small fish,” says Pietsch. “The longlure frogfish’s bait has a black spot on it, mimicking a shrimp eye.”

A black dot — it’s just one more detail further warranting the frogfish obsession.

Scott JohnsonA male yellowhead jawfish aerates a clutch of eggs at Octopus Cave off Cuba.

2. Jawfish

Don’t ask photographer Scott Johnson how long to wait before possibly witnessing a male jawfish aerate — aka hinge open his jaw — to reveal eggs inside.

“Truly, I’ve spent eight hours to sometimes just 30 minutes,” says Johnson.

Start by searching a sand-and-small-rubble field where few big fish or sharks pass. “Even the shadow of a snapper will cause the jawfish to flinch,” he says.

Then look for fish displaying black lines along the ventral area of the head. Should you spy a hole with resident unseen, wait until it appears so you can rule it out or not. One more tip from Johnson: “In the beginning, jawfish eggs are clear to pink, but the more mature they are, the greater the jawfish’s compulsion to aerate — especially when you can see the tiny eyes.”

3. Anemonefish

Christian SkaugeAn anemonefish off the Philippines

“Anemonefish are common but not to be overlooked,” says Ned DeLoach, author of marine-life-identification books.

Especially as overlooking can prove dangerous. This fish can be disproportionately aggressive for its size, like a bunny tackling a bear — which might sound surprising. But then remember that an anemonefish is a damselfish.

In the anemonefish clan, the saddleback proves feistiest, most notably when protecting eggs.

“We were in Lembeh Strait, diving with a lady wearing a hood,” says DeLoach. “The anemonefish bit the top of her hood and got stuck with its teeth in the neoprene. We still tease her about it.”

Granted, the amped-up fish was simply fulfilling its role: Female anemonefish are tasked with nest protection. Up to four or five individuals bunk in one anemone: Find the biggest and you’ve found mama, the lone female.

All anemonefish, including the Clark’s anemonefish (pictured above) begin life as males. When predation or old age claims the matriarch, the next of kin experiences the big change — but in its case, the change is transitioning into the new grand dame.

Then it’s business as usual after the new queen steps up, ready to spar. Which need not be a drawback. In fact, its forwardness might be appealing.

Take the spine-cheeked anemonefish.

“She’s particularly striking,” says DeLoach. “The female will come out toward the diver, making a false charge. Then she really spreads her fins wide, which makes a nice photograph.”

The gesture might fill the frame nicely, but if the stance means anything like hands on hips, then the males back home won’t want to overlook it either.

4. Mandarinfish

Felipe BarrioA mandarinfish off Borneo

For mandarinfish, it’s no different from a bar’s last call when dusk lowers the shade across the reefs of Sipadan, Yap, Palau and other stretches of Asia. The males do everything short of pec-fin wrestling: They flex and strut for female approval. For a front-row seat, scan the coral heads while there’s still light, looking for the highest concentrations, aka tightest-packed watering holes. In the dark, arm yourself with a red light so as not to spook the mating mandarins.

5. Goby

Alex TyrellParagobiodon echinocephalus in Lembeh Strait

Don’t be disappointed if you don’t master your who’s who of gobies. More than 2,000 species are known. Plus, it’s hard to score a long look thanks to a skittish nature combined with a habit of nestling down in branching corals. The redhead coral goby (above) is common in Indonesia’s Lembeh Strait. If you’d like to photograph one, Ned DeLoach offers this: “Find an open place to allow your strobe light to reach them. It’s a challenge, but it just takes time.”

6. Crab

Eduardo SorensenAllopetrolisthes spinifrons – a species of porcelain crab – near Chile

Many macro subjects display behavior at levels too Lilliputian for most divers to appreciate. With crabs, not so. They’re active. Their displays are especially easy to witness among divers willing to pore over identification books, studying their specific environments and cohabitation partners.

In the Indo-Pacific, scan a half-dozen fire urchins — alone worth a gaze for their electric-blue needle tips — and you’ll happen upon the black-and-white stripes of a zebra crab.

Porcelain crabs park themselves only on anemones. “They have appendages that they fan out like tennis rackets, sweeping through the water for plankton,” says Alex Mustard.

Also in the Indo-Pacific, the orangutan crab hangs out only on bubble coral, adorning itself with algae bits as disguise.

“Crabs put a surprising amount of thought into their disguises — they have to because they have such tasty meat,” says Mustard.

Place a crab, like the decorator, into an aquarium with a red backdrop. Then offer him red or yellow felt, and he’ll invariably pick red.

Witness the candy crab. Depending on the soft coral colonized, be it white, pink, yellow or red, the decorator crab will pluck polyps to match, fashioning them on its head and carapace.

Says Mustard, “At night, they’re more confident, standing on the edge of the coral to feed.”

Alex MustardAn amphipod – Iphimedia obesa – off the coast of Scotland

7. Amphipod

“This is an animal few have ever seen — not because it’s rare, but because people hadn’t looked at that scale before,” says Alex Mustard, whose first published photo of an amphipod, which measures roughly a quarter of an inch, garnered a big response. He was on the hunt for nudibranchs when he laid eyes and lens on this.

And what is it?

“Crustaceans are the insects of the sea, and the size range below shrimps are amphipods,” says Mustard. “And this one is bite-size.”

Which might explain why Iphimedia obesa (pictured above), common to Scotland and other areas in the Atlantic, is forever hopping to avoid predation.

8. Anthias

Christian SkaugeAnthias off the coast of Saudi Arabia

Few fish have inspired more nicknames — jewelfish, wreckfish, sea goldies — than anthias. Perhaps it’s due to how numerous they are, shoaling by the thousands. Anthias are distributed widely in nearly every warm marine habitat, save for the Caribbean.

9. Clingfish

Marc CasanovasA clingfish in the Mediterranean Sea

An Apletodon incognitus juvenile (above) often keeps company with urchins. As it grows, the scaleless clingfish — so named for the sucker on its underbelly — trades up for empty mussel shells and algae-covered rocks. Rarely does it live deeper than 60 feet.

10. Boxfish

David HallA boxfish in Lembeh Strait

The juvenile yellow boxfish (above) — a lil’ swimming cube — loves habitats rich with ledges and nooks for hiding because it surprises easily. If overstimulated, it releases a deadly toxin. Boxfish, similar to cowfish minus the horns, inhabit most warm tropical waters.

11. Fairy Basslet

Hilario ItriagoThe fairy basslet, aka the L.A. Laker fish

Sometimes called the “LA Laker fish” for its purple-and-gold stylings, this Caribbean Sea resident prefers teamwork. It lives in hierarchical groups, often on the undersides of ledges. The largest members claim dibs on the choicest plankton-grabbing perches.

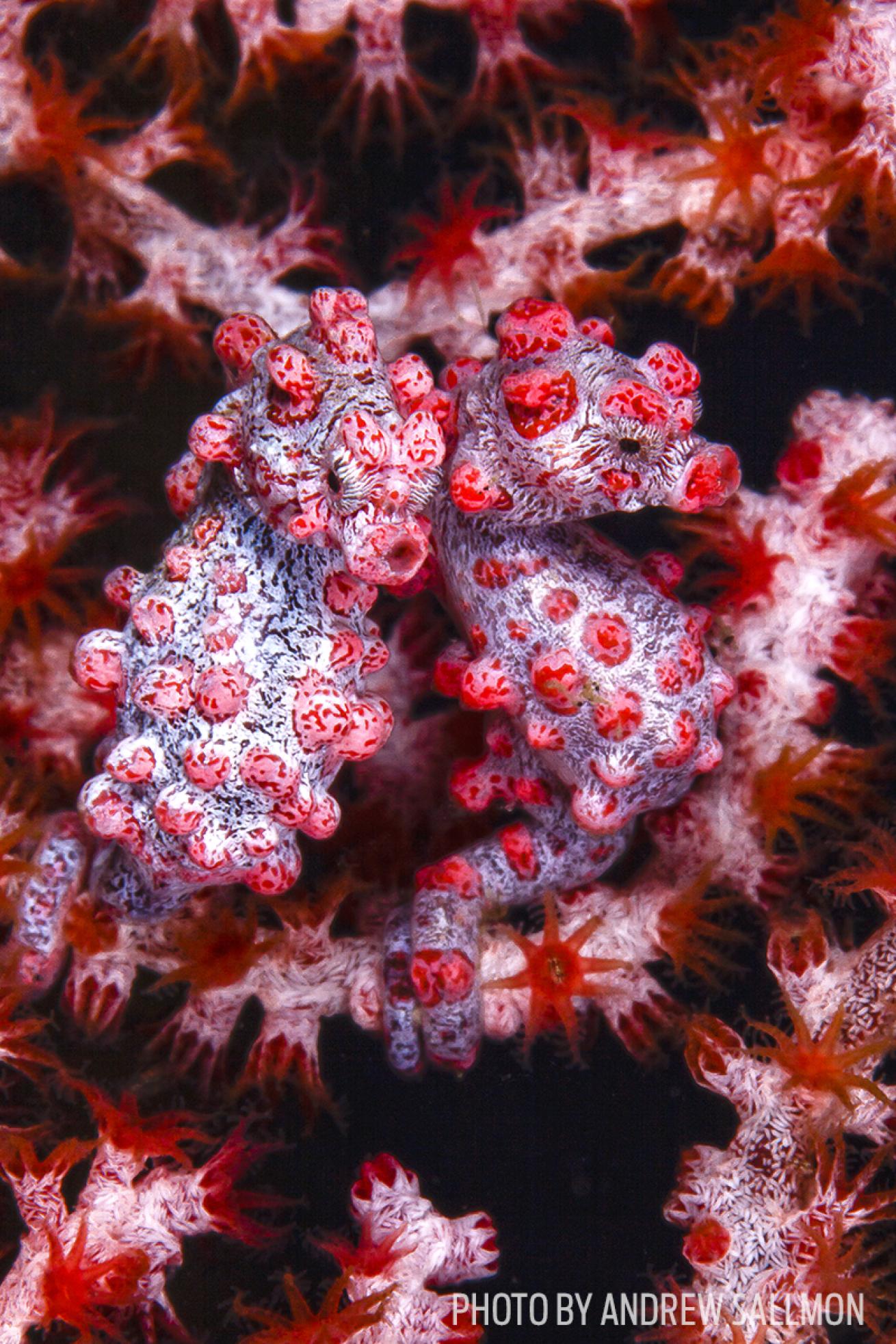

Andrew SallmonA pair of Bargabant's pygmy seahorses in Lembeh Strait

12. Pygmy Seahorse

“Pygmy seahorses are so cute and charismatic that people are instantly hooked — that’s half the danger,” says Richard Smith, a marine biologist specializing in the animal smaller than the tip of your index finger.

Smith wants you to see one in the wild, but he urges divers to stay back several feet from the Muricella gorgonian shelter that Bargibant’s pygmy (right) calls home.

“They stay their whole lives on one gorgonian, and if that gorgonian dies, the pygmy also dies,” says Smith of the seahorses that are thought to spend a few weeks on the current after birth before settling onto their reef homes. And it’s worth noting that the relationship between the seahorse and its gorgonian residence, if left undisturbed, can last for more than 100 years.

That’s not the only factor to consider with pygmy seahorses. These beautiful photo subjects have no eyelids and are extremely sensitive to bright lights, such as flashlights and excessive strobe flashes. Shutterbugs should keep this in mind when observing or photographing them.

Instead of aiming to fin closer, stay and watch.

The Bargibant’s pygmy is more of a homebody, but, says Smith, “Denise’s pygmy seahorses are super-active by comparison, hopping from one holdfast to another.”

He adds, “I watched a female let go of a gorgonian and swim 8 inches, which, when you’re only three-quarters of an inch long, is epic.”

13. Nudibranchs

“I’m so fascinated by the 3,500 described species because of the biodiversity in every aspect of their being: color, shape, size, and how they breathe, feed, reproduce and defend themselves,” says David Behrens, author of the book Nudibranch Behavior. Take their breathing. Every animal pictured below utilizes different respiratory organs, from the ruffles of Elysia crispata to the gill branches of the Marionia. And the nudibranch biodiversity count climbs yearly. Behrens’ most recent research expedition to Anilao, Philippines, resulted in locating at least eight previously undescribed species.

Gary Bell/Oceanwide ImagesThe Eye Test

“Marionias are almost impossible to identify correctly with the naked eye,” says Behrens. “They’re so varied in color.”

Felipe BarrioSuper-Sniffer

“The hornlike structure, called rhinophores, is the smelling organ,” says Behrens. “It’s how they find food and mates.”

Felipe BarrioSmall Slugs

While nudibranchs can grow to be as large as 12 inches in length, Stiliger ornatus is only a couple of millimeters long.

Felipe BarrioSpit Take

Phyllidia coelestis secretes acid quickly, often with little provocation — causing the fish or other predator to spit it out.

Greg LeCoeurOdd Anatomy

“Like humans, nudibranchs have a jaw, teeth and a tongue. But unlike humans, they are all in different places,” says Behrens.

Jurgen FreundBonus Babies

All nudibranchs are hermaphroditic. A couple of Nembrotha kubaryana, seen mating below, will result in two pairs of eggs.

14. Blenny

Jose Alejandro AlvarezA red-spotted barnacle blenny

“I love blennies because they’re so accessible,” says Anna DeLoach, researcher and founder of the Blenny Watcher Blog.

“I can take you on almost any saltwater dive and find you one or more species; the same can’t be said for most other fishes,” she says.

Her favorite Caribbean species, the sailfin, is something of an entryway blenny.

“The sailfin is the one that gets divers excited about blenny hunting. I tell people to swim over the rubble plain at 4 p.m. and look for these little black fish, flapping their huge — for them — dorsal fins.” If that high leaves you wanting more, DeLoach can steer you to another to match your tastes. For a photogenic pick, try the tessellated blenny, much like the barnaclebill blenny pictured above. For drama, she says, “Hang around a colony of spinyheads or pike blennies — you’re sure to see a few fights and mating displays.” For weird, try the fangblenny. Yup. It has teeth.

Then, read up on its hangouts. Just like Ernest Hemingway warmed the seats of Harry’s Bar, so too do these guys haunt very specific lairs.

“Tessellated blennies live in barnacle shells and abandoned worm tubes in high, shallow places, like dock pilings and mooring lines,” says DeLoach. Accessible and prevalent, yes. And thanks to researchers like DeLoach, their habitats are described just short of GPS coordinates.

Bruce ShaferA juvenile shrimpfish off Anilao

15. Shrimpfish

It seems impossible: The shrimpfish swims with its head straight down. Even trumpetfish tip into an arrowlike position before darting forward.

Blame, or credit, biology. Like a bunch of firewood kindling, the shrimpfish’s dorsal spine, dorsal fin, causal fin and anal fin are bundled together, one atop another. This is possible due to an extremely stable internal configuration.

“Its center of buoyancy, which wants to pull the fish up, is behind — almost at the same level as — its center of gravity,” says Frank Fish, professor of biology at West Chester University in Pennsylvania. “Why it does this is curious — it’s a way of hiding.”

16. Octopus

Jenny StromvollOctopuses can be found off the coast of Mozambique, where this juvenile — too young to be identified by species — was spotted.

Masters of camouflage, even octopuses are blind to the bad habit that betrays their middens. “They’re messy in their housekeeping,” says cephalopod scientist Roger Hanlon.

Species such as the Caribbean reef octopus throw the day’s trash — clam and crab shells — just outside the front door. If nobody’s home, try coming back in the morning when the mollusk leaves to hunt.

Says Hanlon, “Then you can watch as it changes camouflage pattern every time it lands on new substrate — it’s one of the most magical, mindboggling things they do.”

Liz HarlinA wire coral shrimp off Indonesia

17. Shrimp

Eye shine — that nighttime effect when dive lights reflect red in certain peepers — makes spotting shrimp after sunset much breezier. Eerie, perhaps, but breezier. It’s a cheat, really, to flush out these otherwise well-hidden invertebrates, like the wire coral shrimp (right) that so adroitly mimics the color of its host. So much so that by day, it’s a find that most divers need training to locate.

18. Hawkfish

Scott JohnsonOxycirrhites typus, pictured off Palau

The average hawkfish meet-and-greet lasts just four seconds. Once wary, the fish darts from view. Luckily, he resets — that is, hops between a handful of locations before returning to that original meeting spot.

“Watch and you learn their favorite perches, typically just two or three,” says Ned DeLoach.

Within a few minutes, it’ll cycle through and once more you can observe it in all its splendor.

“Not only is this a dramatic fish in terms of morphology — colors, that is — but it inhabits soft corals and gorgonians, which are such pretty backgrounds,” says DeLoach.

One, Paracirrhites xanthus, is solid gold, giving new meaning to the term “money shot.”

The Caribbean houses just one species, the redspotted hawkfish; the rest — like Oxycirrhites typus (pictured above) — are mainly in the Pacific and around places like Indonesia.

It’s fitting that DeLoach, a photographer, claims his favorite as one of the most photogenic: the flame hawkfish. Its body is a deep reddish orange, like a ripe mango. Around its eyes are half-circles of black, as if lined with smoky kohl.

Adds the man who’s taken stills of them all, “The flame also happens to be the hardest to shoot.”

Even armed with the knowledge that they flit between just a couple of perches, DeLoach says, “It’ll take you the better part of a dive to get a shot, but, boy, are they worth it.”

Jordi BenitezSpirobranchus giganteus, pictured in Bonaire

19. Christmas Tree Worms

One name, Spirobranchus giganteus, includes every color variation — be it blue, white, red, orange or yellow — of this sedentary segmented worm. Each individual is actually two trees, which serve as gills — as well as nets to collect plankton meals. These worms are famous for spooking easily from bubbles or even a shadow. Luckily, they typically reappear within the minute.

20. Leafy Seadragon

Todd AkiA juvenile leafy sea dragon off the coast of Australia

Don’t make the mistake of thinking these camouflage masters — often called leafies — are seahorses. They’re pipefish, spanning up to 12 inches from snout to dragon tail. They might be big in the macro world, but their range is relatively small. They undulate only along Australia’s southern coast, from Adelaide to Perth. And they keep to themselves, staying within an area 33 feet by 33 feet in open areas near jetties, such as that of Wool Bay and Edithburgh.

Love discovering creatures in the ocean? Find more exciting places to visit on the Travel section of our website.