How An Experienced Scuba Diver Ended Up In A Solo Dive Emergency

Hindsight can be helpful. And humbling. When I look back to a certain submersion off Tongue Point on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, when my mistakes were manifold and the dive went south in a big way, I curse myself for a fool. I also attempt to comfort myself, saying that it could have been worse and that I’ve learned from the experience.

Brandon ColeSalt Creek's thick bull kelp and current presents tricky conditions.

I arrived late at Salt Creek. I geared up quickly, grabbed my camera and scrabbled down the rocks and through tide pools, a clumsy mountain goat in scuba gear, eager to explore one of the Northwest’s best shore sites. I caught my breath and surveyed the scene. A bit windier than yesterday’s forecast for today. Foggy out in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, a gray gauze partially obscuring what I knew to be a stunning view. Frothy in the shallows, waves slapping against the rugged shoreline, surge pulling at the water beneath me. But I didn’t get all kitted up for nothing. I jumped in.

Relieved to be in the water — you can definitely psyche yourself out standing atop the rocks for too long — I began the long surface swim. I wanted to get out to a deeper reef beyond the kelp. That kelp, annoyingly thick, seemed hellbent on slowing me down, repeatedly snagging my fin straps, tank valve and camera. Frustrated, I decided to drop down and swim underneath the canopy, blowing through a few hundred pounds of air. Finally on the kelp forest’s far side, there was more current than I expected. Apparently, I had missed slack, or the predicted time was incorrect — not uncommon during large tidal exchanges. I bombed down to the bottom. Thanks to the dive shop’s short fill, my gauge read 2,400 psi when I touched down in 50 feet.

Critters and color were everywhere. I was instantly reminded of why I liked Salt Creek. But on this day, visibility was poor, and both current and surge were strong. I found cool photo subjects aplenty, but had great difficulty photographing. A half-hour into the dive, and the current, if anything, had strengthened. But I wouldn’t give up. I stuck with my (bad) plan for another 20 minutes before admitting defeat and ascending.

Brandon ColeSalt Creek is known for its diverse marine life, such as this fish-eating anemone.

The weather had deteriorated significantly. The fog was thicker. The waves had picked up. And still the incessant current. I couldn’t see any kelp. Where was I? Which way to shore? My compass was useless. It had started acting up a week ago, and I hadn’t replaced it. I heard a boat, somewhere, but couldn’t see it. Reckoning it was in the middle of the strait, I swam in the direction opposite of where I thought I heard the boat. When the fog lifted maybe 15 minutes later, I saw that I had been kicking the wrong way. I was angry and alarmed. I could see the kelp bed, and the wave-battered shoreline beyond. Salvation was at least a hard 30-minute swim away. I cursed my compass, the weather, my bad luck, my stubbornness. I would have yelled at my dive buddy too, but I didn’t have one.

Adrenaline powered me to the kelp. With my tank nearly empty, I had to fight through the tangle on the surface. My pony bottle (in the car) sure would have helped. By the time I made it through the jungle, the wind had increased to 20 knots, and waves were hurling themselves against the rocks. Plus, the tide had dropped. I faced a cliff for my exit. No way. Berating myself for jumping off the rocks in the first place, I swam to another place I thought might be easier to exit.

Brandon ColeBrandon Cole is a wildlife photographer whose work appears regularly in Sport Diver. He lives in Spokane, Washington, and often dives off the Olympic Peninsula with his wife Melissa.

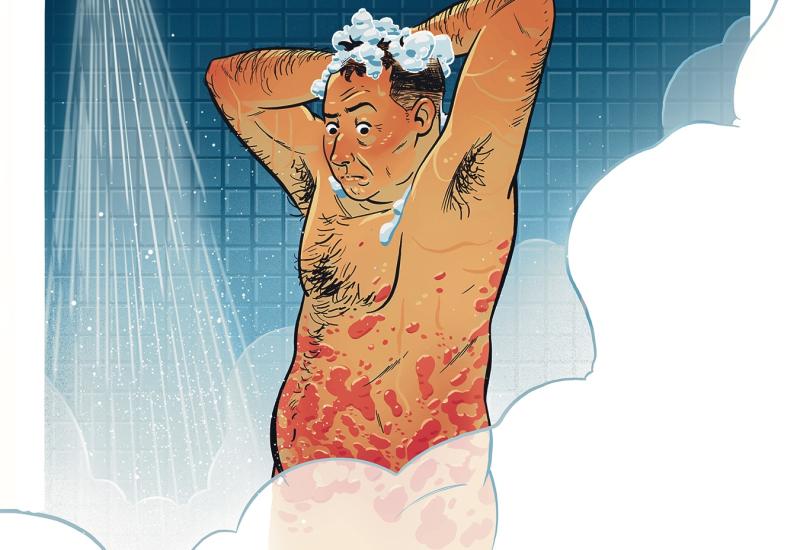

I tried to ride an incoming swell up onto the rock platform. The wave creamed me. I hit hard, clung in desperation and then lost it completely, falling badly and hurting my wrist while trying to protect my camera. (Later I would learn that one strobe flooded from the impact, and my housing’s port was scratched to ruin by barnacles.) My leg was wedged into a crevice, and the rocks tore a big gash in my drysuit. The next wave tumbled me backward into the ocean. Near panic, I kicked away from the rocks. My suit was full of water now. I ditched my weights and manually inflated my BC. I was shaking, and not just from the cold. I screamed at the world.

My savior — a man in a fishing boat zooming east outside of the kelp bed — didn’t hear me. But he did see me flailing about, waving my hands frantically. His boat slowed, and then turned toward me. When he pulled up alongside me and asked if I was OK, I didn’t know how to answer. Perhaps my wild eyes said enough. He invited me on board.

When I told him about my dive, I found myself almost in disbelief recounting just what I had done, and not done. How could I have been so careless, so many times? My poor judgment, at many stages before and during the dive, had turbocharged Murphy’s law, resulting in a near nightmare.

Epilogue: A few months later, I returned to Salt Creek with a friend. Exercising more care in preparation and execution, we enjoyed a wonderful dive.