Digital Photography 101: Muck Diving Photo Tips

Gil Woolley/ScubazooOpistognathus sp, mouthbrooding eggs, Kapalai, Borneo. Getting close shows the detail in the eyes and removes the rubble background.

Gil Woolley/ScubazooNemateleotris magnifica on Mabul Island, Borneo. The strobes were angled to only catch the fish and not the rubble substrate behind.

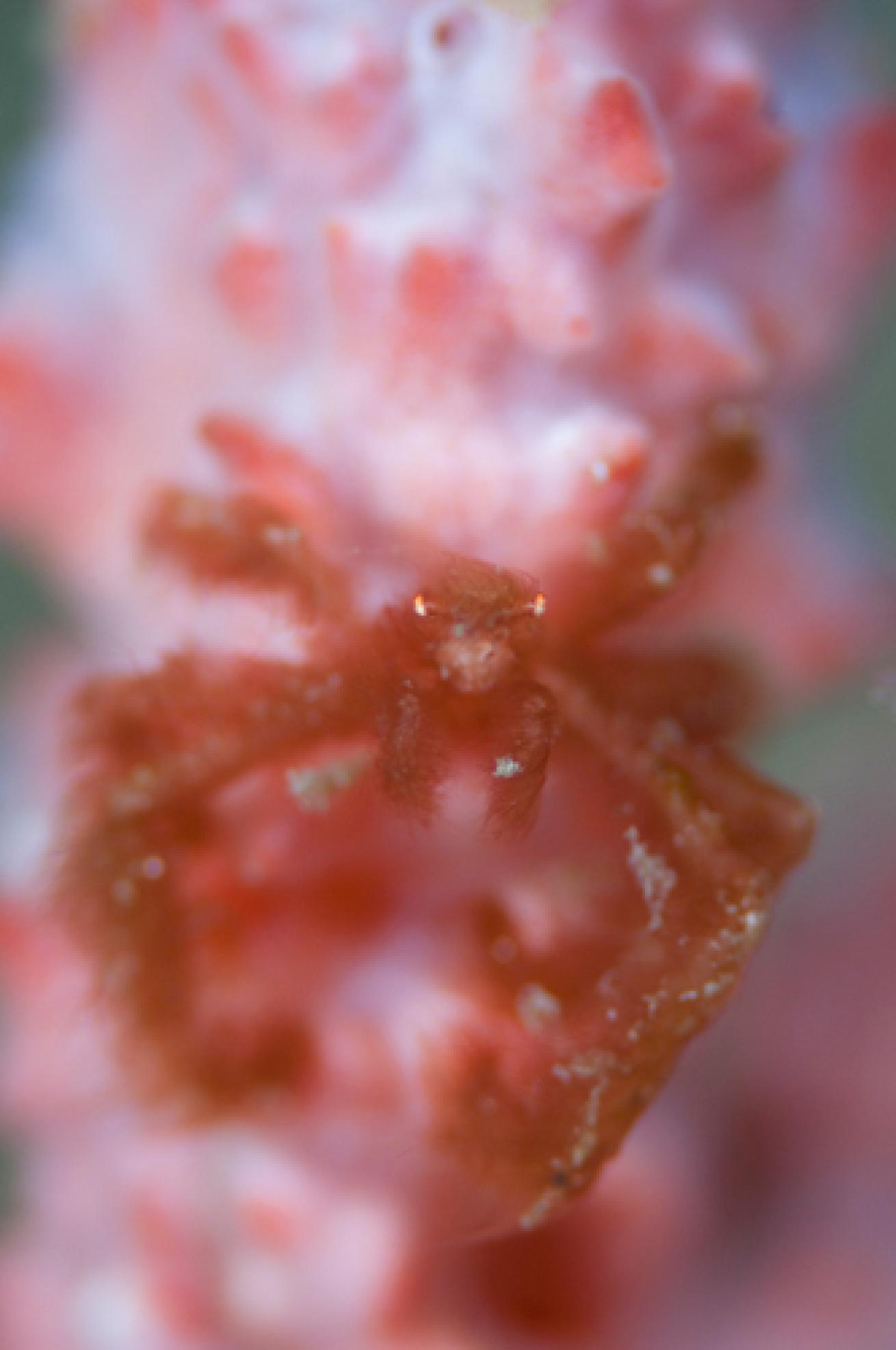

Jason Isley/ScubazooAchaeus japonicus, Lembeh Strait, Indonesia. Critters often match the colour of the objects around them for camouflage.

Jason Isley/ScubazooDendrochirus brachypterus, amongst flamboyant cuttlefish eggs, Mabul, Borneo. Once you get your eye in, you will start to find subjects everywhere!

Jason Isley/ScubazooPapilloculiceps longiceps, Mabul, Borneo. Spending time with subjects often results in witnessing their behaviour, making more interesting shots.

Christian Loader/ScubazooPhycocaris simulans, Timba Timba, Borneo. Shooting upwards with a low depth of field removes the background.

Jason Isley/ScubazooAcrochordus javanicus, with algae growing on its back. Semporna Straits, Borneo. Taking the time to wait for eye contact and a protruding tongue can really improve a shot.

Gil Woolley/ScubazooSynchiropus picturatus, Semporna Straits, Borneo. The old fishing net that is home to this fish proves a handy frame for the subject.

Gil Woolley/ScubazooRhinopias frondosa, in East Timor. The spines of a sea urchin behind the fish provide an unusual background.

Gil Woolley/ScubazooHippocampus hystrix, East Timor. The shallow depth of field hides the dull black sand behind.

For a photographer, muck diving can be one of the most rewarding and enjoyable ways to spend time underwater. But what exactly is a "muck dive"? There are many definitions out there and I am not going to argue the finer points of each, but to me, it is a dive on muddy or silty substrate, rubble or black sand, where visibility may not always be great, but it doesn't really matter as most of your subjects lay well hidden on the sea floor. Basically, if someone says they are taking you for a muck dive, make sure you have our macro setup ready, and don't expect pristine coral reefs in 25-plus-metre visibility with pelagic species swimming all around you.

My standard setup for a muck dive is: Nikon SLR with 105mm macro lens, two Inon strobes, a spotting light and a +10 wet diopter. The wet diopter is always a good idea for SLR and compact setups as many of the most interesting species tend to be very small.

To get the most out of a muck dive with your camera, there are a few simple steps to follow.

1. Firstly, the substrate. This can be your friend and your worst enemy at the same time. On the plus side, there is usually a place where you can safely rest an elbow or a knee to steady yourself when shooting, as long as you follow the golden rule and make sure you are not damaging any marine life and you have taken care to make sure there are no creatures buried in the sand where you will be resting, especially ones with spines. The downside is the substrate is usually very silty on a muck dive, so every time you touch the bottom or reposition yourself, you are likely to disturb huge clouds of particles that will obscure your subject and cause backscatter in your image.

2. Plan your dive. Muck dives are often in relatively shallow water, so use this to your advantage. Your tank will last longer in shallow water, giving you more bottom time with your subjects, especially when waiting for behaviour (more on this later). Talk with your dive guide and boatman and plan to maybe do three longer dives in a day rather than squeeze in four normal dives.

3. Patience. On your first dive, make sure you don't get carried away swimming madly around trying to look for subjects. Take your time, go slowly and keep as close to the substrate as you can, making sure you are not kicking the bottom or stirring up clouds of sand for the annoyed divers behind you. It takes a while to "get your eye in" with well-camouflaged macro subjects, so make sure you don't get frustrated. On flat sandy seabeds, it is worth searching around any object where critters might gather, be it an old log or a coral bommie. It goes without saying that a good guide is invaluable for this kind of diving.

4. More patience. Once you have found a subject that you want to photograph, again, it is worth taking your time. Approach slowly so as not to spook the critter. Position yourself slowly and carefully so as not to disturb the sediment or damage any marine life. Wait patiently for the subject to do what you want it to do, whether that is face the camera, yawn, or any other behaviour you are trying to capture. Don't give up. Wait a bit longer as that frogfish is bound to yawn soon! Make sure you keep an eye on your gauges though and always put safety first. I often attach my dive computer to my camera housing so I can check my depth and bottom time with a small rotation of the head, reducing movement that is likely to disturb the sediment.

5. Consideration. Dive operators frequenting muck sites are usually very considerate to photographers and will dive in smallish groups and will wait for everyone to have their turn at shooting. Make sure you are considerate too — give other photographers a chance and don't get carried away with Tip No. 4 (unless everyone else has had their turn). If you are lucky (or rich) enough to have your own guide, it is a good idea to discuss a plan with them before you enter the water. Once you find something to photograph, tell the guide that you might be some time and agree with them in advance that they should search the nearby area for more subjects. You can then move from one shot to the next, removing the frustrating searching time.

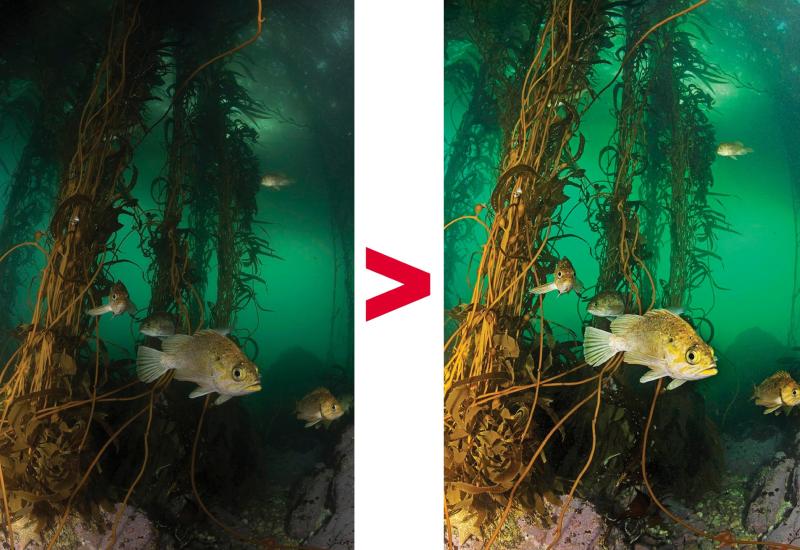

6. Background. One of the main issues with your images taken during muck dives will be the background of your shot. You may have the subject beautifully lit and the eye in sharp focus, but a muddy brown, drab background rarely adds to your image. There are several techniques you can use to overcome this. Firstly, position yourself so the subject has a more interesting background, even open water if you can get low enough. Or, use a high f-stop — such as 5.6 or higher — to blow the background completely out of focus. This can also work very well when the colour of the subject is the same as the background, like a red hairy shrimp on red algae, giving a Bokeh effect. Lastly, position your strobes or use a snoot to only light your subject and not the background.

7. Get close. Stealth is a handy tool to have on your side and as mentioned, approach your subject cautiously so as not to spook it. The technique of getting your camera and strobes set up in advance and taking test shots is a very good idea so you know you are ready to shoot as soon as you are in position. Subjects are often very small so you need to get close to fill your frame, which is another way of removing unwanted backgrounds. A wet diopter is a handy way to increase the magnification allowing small subjects to fill the frame.

Muck diving is not for everyone, as the sites are often unattractive and strewn with rubbish. I have shared dives many times with a drifting nappy (diaper for my American friends). However, if you can get past this, enjoy weirder critters and have a keen eye, good sites can prove to be heaven for the underwater photographer.

Gil Woolley (38, UK) is a photographer, publisher and library manager for Scubazoo Images. He has been involved with natural history imagery for the past 17 years as an editor, creative director and photographer, now based in Sabah on the island of Borneo.