The Manta Trust: Fighting to Protect Rays From the Gill Raker Trade

Guy Stevens

Shawn Heinrichs

Paul Hilton

Guy Stevens

Guy Stevens

My watch reads 6:15 p.m. — 20 minutes until we need to surface to make it back before sundown. For the past half-hour, we’ve been searching through a field of elephant-size boulders just off Socorro Island in Mexico’s Revillagigedo Archipelago for an acoustic-receiver station, but the buoy holding it high above the rugged seafloor is nowhere to be found, likely destroyed during a storm. With the new receiver clipped to my BCD — along with five feet of chain, 15 feet of line and a trawling buoy to keep it all upright — I search awkwardly through crevasses in the massive rubble. I hear shouts muffled by bubbles nearby as a great hammerhead streaks through the corner of my vision. Guy Stevens, marine biologist and director of the Manta Trust, and Dr. Robert Rubin, director of the Pacific Manta Research Group, beckon eagerly. They’ve found the receiver, buried underneath a rock and barely visible save for a few inches of chain.

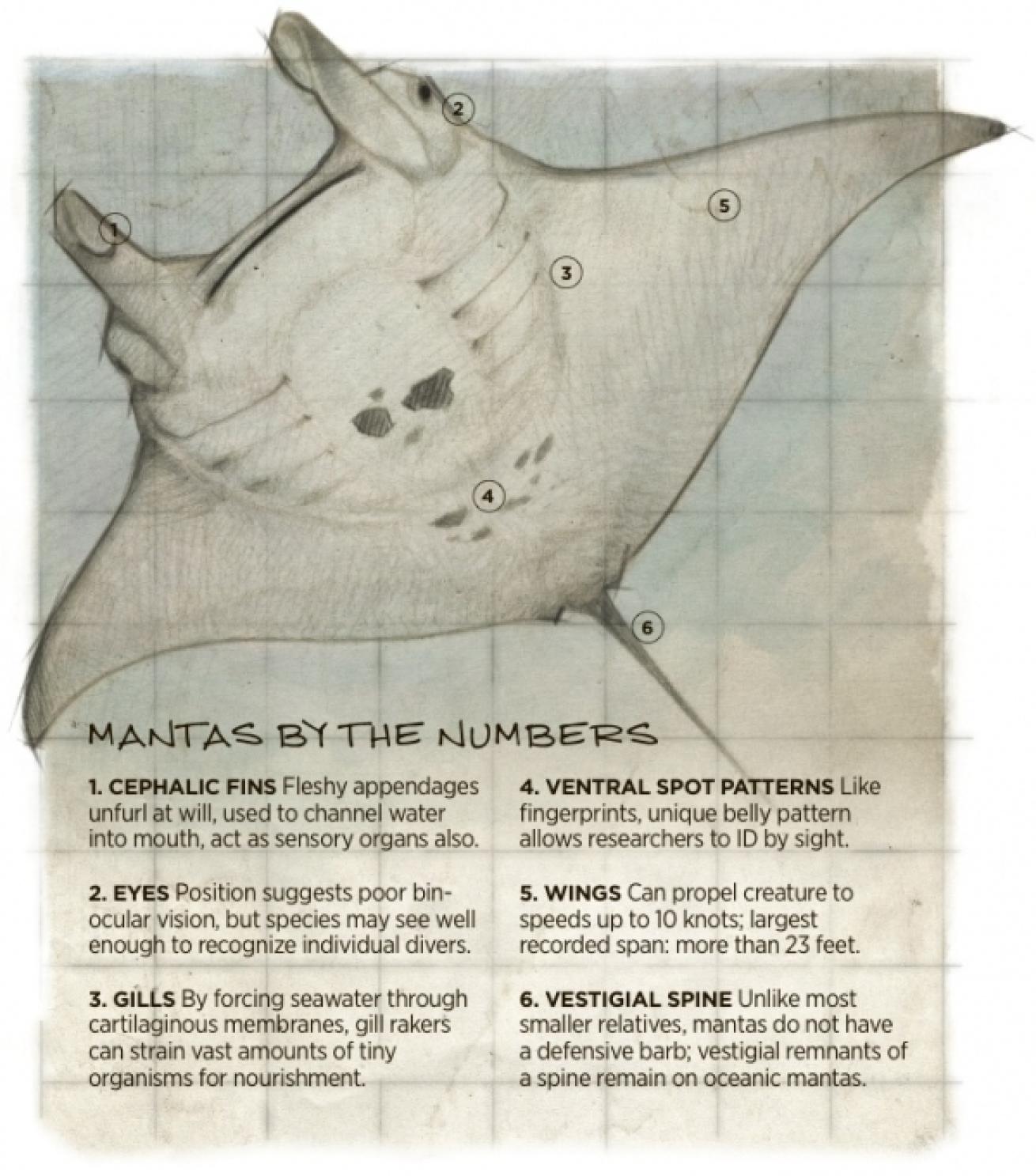

Rubin cuts the old chain, weakened by a year of rubbing against the rocks, and I attach the new receiver in its place. A huge shadow engulfs us. Confused, we look toward the surface, wondering if the dinghy captain is growing impatient. The late-afternoon sun has been blocked by a massive oceanic manta ray — practically 15 feet across — gliding overhead. Stevens digs out of his pocket a small point-and-shoot camera, and grabs an ID shot. The spot pattern on a manta ray’s belly is unique to each animal and can be used to identify it, much like fingerprints. The manta banks back sharply, as if to watch our work, making three more passes before we’re done. Now that we’re up in the water column, he flies within inches of our heads, taking a moment to make direct eye contact each time.

Soon another joins us, an even bigger female — 18 feet across. She’s on a collision course with the smaller male, but inches from disaster they both pull up into graceful somersaults, bellies practically touching as they slowly roll away. The acrobatics continue as a third manta arrives, this one a small male with a gnarled tail. So far, none has an acoustic tag tethered to its back that would communicate with the receiver we’ve collected. As the light underwater dims to twilight, a fourth manta joins the group. We’ve pushed a few minutes past our deadline and surface, reluctantly leaving the mantas behind. Watching the giants circling gracefully below us, I wonder: Where have they traveled? Where are they going? How much of the vast, unexplored oceans have they seen?

Rubin, Stevens and I have come to Las Islas Revillagigedos, Mexico — also known as the Socorro Islands — to start piecing together the puzzle. While Stevens’ extensive research of the Maldives’ Hanifaru Lagoon has led to a much better understanding of reef manta rays, their larger relatives — oceanic mantas — remain a mystery. In these remote islands, the Pacific Manta Research Group — the longest-running research program on oceanic mantas — has been collecting population data for more than 30 years. Rubin has cataloged thousands of photographs of the ventral spot patterns of visiting mantas, gleaning more than you might think possible. The photos reveal not only how many individuals make up the population, but also when and how often they’re around, if they form associations with each other, and what they’re doing — whether they are at a site associated with feeding or cleaning behavior, for example. But this research site is extremely remote, so it’s impossible to collect reliable data year-round, even with dive boats contributing manta-ID photos from their frequent excursions. As a result, Rubin and Stevens have turned to more high-tech methods.

SCIENTIFIC GOLD

Back aboard the boat, I peel off the first encrusted layer of plumber’s tape that protects the receiver like I’m digging down to buried treasure. Acoustic- receiver stations listen for tags, which in this case are attached to 19 oceanic mantas. A unique set of high-frequency pings that identifies each tag allows scientists to collect data on any tagged animal within a 1-kilometer radius of a station over about a year. Buried underneath half a dozen layers of protective tape is a trove of information indicating which mantas were in the area, how long they stayed, how often they visited, and when they were there. With a dozen stations scattered throughout the islands listening intently for nearby mantas — or any other animals with acoustic tags — scientists can see an even better picture of how mantas are traveling between the islands and what they’re doing.

READ ABOUT THE MANTA TRUST'S WORK IN THE MALDIVES.

With each new discovery, however, more questions arise. While acoustic data provides an idea of what the mantas are doing within the archipelago, it also confirms that most of the time, they’re elsewhere. Rubin’s years of photographic data support this conclusion: Roughly 95 percent of the estimated local population is absent from the islands at any given time, suggesting it is only a temporary stopover. And with gaps in sightings upwards of 18 years, what do individual mantas do in between? Are they just out of range of the receivers, or are they traversing the world’s oceans, making their way across the Pacific, into the Indian Ocean and back, to be spotted years later?

Increasingly, these questions are becoming less scientific curiosity and more dire conservation concern.

TO KILL FOR A GILL

The amazing mechanism that allows massive mantas to thrive on miniscule krill and zooplankton — the highly specialized gill raker — is also the cause of the species greatest threat.

All fish possess gill rakers, hard cartilage on the inside of their gills that protects the fragile gas-exchangers from damage when the fish eats, and a lot can be learned about the feeding habits of a fish based on these structures. Manta rakers have evolved into a tight-knit, feathery structure that excels at straining plankton. Swimming, barrel-rolling and whirling through thick patches of zooplankton, mantas simply open their mouths and allow seawater to flow over their gill rakers, straining out the tiny but valuable food. It is this function — the filtering action — that has put manta populations in danger.

Traditional Chinese medicine often claims cures for minor human ailments by emulating the structure or function of wild plants and animals. Unfortunately, the products are often collected to the detriment of threatened species, including tigers, rhinoceros, sharks and mantas. Similar to the shark-fin trade, the only part of a manta coveted for traditional Chinese medicine is the gill raker. Supposedly its natural filtering ability allows it to take impurities out of the blood, treating ailments such as thyroid disorders. But unlike many traditional products, gill rakers as a remedy do not seem to be “traditional” — they appear to have been invented and inserted into practice within the past decade or so, according to research by the Manta Ray of Hope project.

While bycatch of mantas in pelagic fisheries was likely already impacting their populations, now targeted fisheries have cropped up around the world in response to growing demand. Throughout Indonesia and Sri Lanka, as well as parts of Africa and South America, tens of thousands of mantas and mobula rays are being slaughtered each year. Since the meat is of low quality, the only parts of value are the rakers; it’s not uncommon to see just the head of a large manta brought into a fish market.

Investigations of markets in mainland China, Hong Kong and Singapore by Manta Ray of Hope have discovered numerous shops carrying anywhere from a handful of manta and mobula rakers to bags upon bags containing hundreds, perhaps thousands, of dried gill rakers. Shopkeepers relate that demand has re- mained consistent over the past 10 years, while supply has been more and more difficult to obtain — an ominous sign that might indicate a decline in glob- al populations. Preliminary fisheries reports gathered by the Manta Trust in Sri Lanka estimated as many as 55,000 mobula rays — and more than 1,000 mantas — being hauled into the country’s fish markets every year.

While a few thousand mantas each year might not sound like much, these amounts might be hugely damaging to manta populations: Consider that over the past 30 years, Rubin has identified fewer than 400 individual mantas in Socorro. Manta populations do not appear to be large, and they’re very vulnerable to exploitation. A mature female manta gives birth to only one pup at a time after 13 months of pregnancy, and most likely only once every two to five years. This slow population growth causes a striking inability to quickly replace large numbers of mantas removed from the population.

The good news is that mantas are at the top of every diver’s must-see list — a strong economic incentive for the species to be protected.

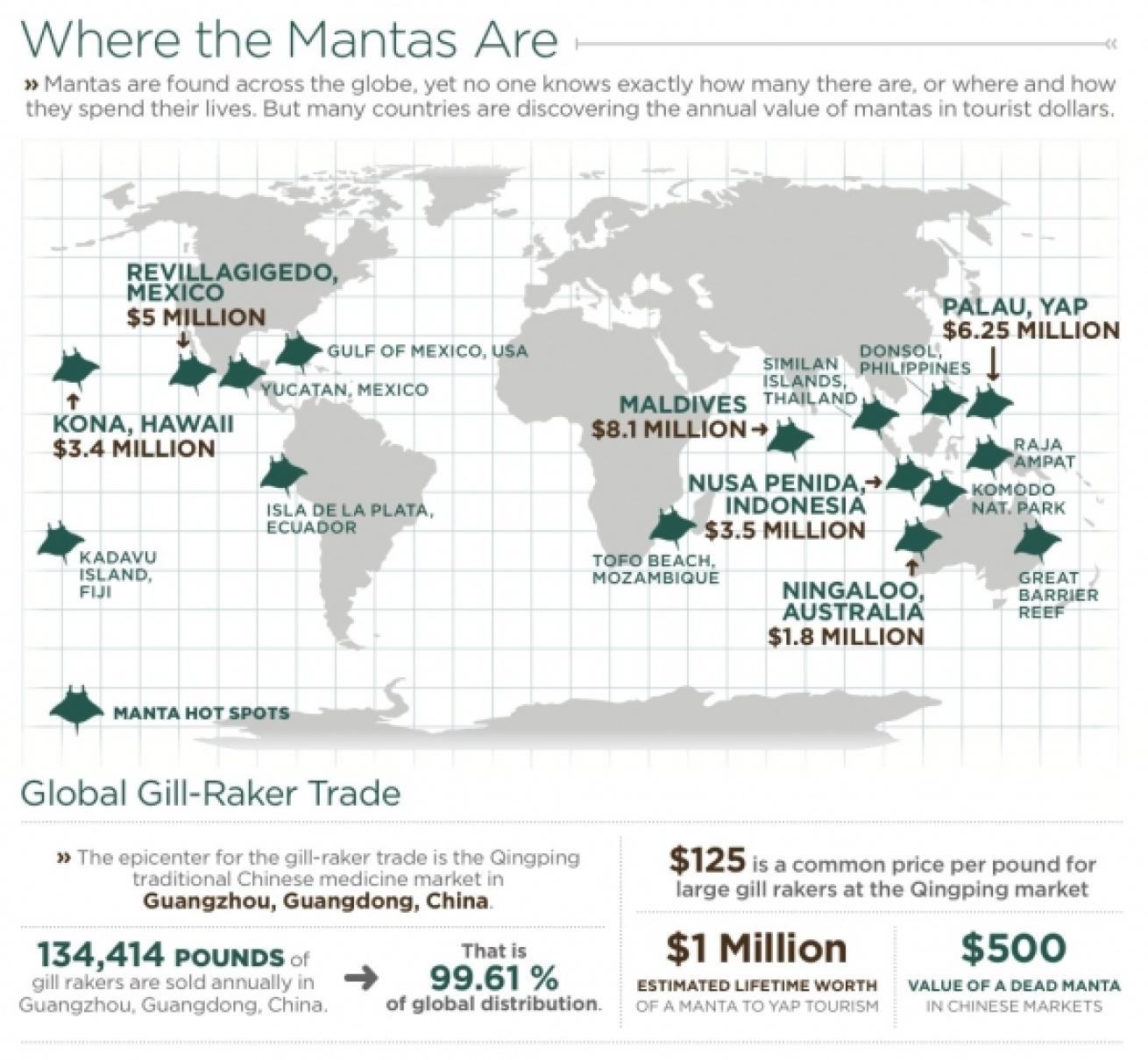

The Maldives brings in more than $8 million a year in manta tourism, so the country has banned the export of all shark and ray products, choosing to value them as a sustainable ecotourism resource rather than as an unsustainable fishing product.

Similarly, Mexico — with an estimated $5 million in revenue from manta tourism — has protected the species and levies stiff fines for killing a manta.

Still, our knowledge of oceanic mantas remains inadequate. Without understanding their migration routes, where they spend the majority of their time, how far they travel and what their critical habitats are, it will be very difficult to effectively protect the species. For example, we need to know if these animals can be protected within one country’s jurisdiction, or if it will require international cooperation. And if protection is possible, is the best approach to protect the individual animals, or to safeguard the habitats crucial for their continued survival?

The Manta Trust was created to answer these questions, to educate local communities on the value of sustainable manta tourism, and to encourage governments to take proactive steps in protection and conservation.

How can you help? By continuing to dive and snorkel with mantas around the world, providing a valuable alternative to exploitation.