ZEROVIZ: Tampa Police Department Dive Team

“Gear up guys, we’re almost on ’em.”

The call from a crewmember on the Hatteras 54 stirred Carl Giguere and Louis Vazquez from their racks. As they pulled on dive skins and checked their small, lightweight SCBAs (composite-material Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus designed for firefighting) modified for SCUBA, they agreed that the night’s activities were a departure from “same-old, same-old.”

Once on deck, they assessed their situation. A Coast Guard cutter stood off from a large ocean-going freighter, which obscured much of the dark horizon on the Gulf of Mexico. Cutter spotlights and the freighter’s own deck lighting made a stark image against the backdrop of black water and night sky. Crew from one of the cutter’s boats threw long shadows as they climbed onto the freighter per their boarding protocol. The Hatteras slid through the water toward the freighter’s stern.

Hidden Cargo

A few hours earlier, Giguere and Vazquez had boarded the Hatteras in Tampa, Florida, at the request of U.S. Customs agents who had an interest in the foreign-flagged freighter; the night’s party would be jointly hosted by U.S. Customs, U.S. Coast Guard and the Tampa PD Dive Team.

The predive briefing by customs covered what the divers needed to know for their part. Customs had credible information that the target vessel was carrying a large quantity of marijuana in its rudder compartment, and they were interested in determining its final destination. Whether the captain or crew of the ship had knowledge of the contraband cargo was unknown.

On large ships, the area where the rudderpost enters the stern of the ship is housed in a small compartment accessible by water from underneath the hull. Smugglers will also utilize sea chests, openings in a ship’s hull used for cooling intakes and covered by a removable grate. Ships in port or at anchor sometimes take on cargo in these compartments, which is not listed on the manifest. Delivery of contraband can be made by boat if the ship isn’t loaded, or by divers if the ship is sitting low and access from outside the hull is submerged. Depending on the value of the shipment or the whims of the shipper, chaperones may also stow away in the compartment as investment security consultants. Accommodations are less than luxurious.

The Dive

Giguere and Vazquez slid into the warm Gulf waters and faced a surface swim of several hundred feet. Under the looming swell of the stern they submerged and located their access point after a brief search. Surfacing in the compartment, their lights picked out a web of ropes crisscrossing the opening and bales of marijuana wrapped in dark plastic on the ledges above the ropes.

Now their job was to attach a small, inconspicuous transmitter to one of the bales. A thin wire running from the transmitter was designed to part if the bale was moved and caused the transmitter to begin announcing its location to monitors. The smaller size and lighter weight of the modified SCBA setup paid off as they completed their task in crowded quarters.

With the transmitter in place, they reversed their route and dropped back through the access and resurfaced in the Gulf for the swim back to the Hatteras. Total time from splash to recovery was about one hour. With the divers back aboard the Hatteras, the Coast Guard boarding crew returned to their cutter and the three vessels departed the rendezvous on divergent courses.

**Useful Intelligence **

Giguere and Vazquez never learned the outcome of the exercise. If crew aboard the freighter knew of the marijuana it’s possible they were aware of the divers’ activities and tipped off those assigned to remove it from the compartment. No attempts to retrieve it were made while the ship was in Tampa and under surveillance. But even forcing the smugglers to change routine may provide useful intelligence.

It’s not uncommon for outside agencies to request the services of police dive teams. Organizations with infrequent need for underwater investigative services tend to contact local police for dive services provided by well-trained divers who are also aware of evidence collection and chain-of-evidence procedures. Post 9/11 concerns have ramped up the need for divers trained in vessel searches, underwater structure security and explosive ordnance recognition and disposal (EOD). Larger departments such as Tampa PD and county and state units will usually provide dive services to departments with limited resources upon request, and to most of the divers attached to part-time dive units a bad day diving is a good day at work.

_Charles “Chuck” Ford was scuba certified in 1974 in Monterey, CA, while stationed with the U.S. Navy. A retired member of the N.Y. State Police, he served on the Troop D Dive Team for 18 years, several of those years as Troop D Senior Diver.

_

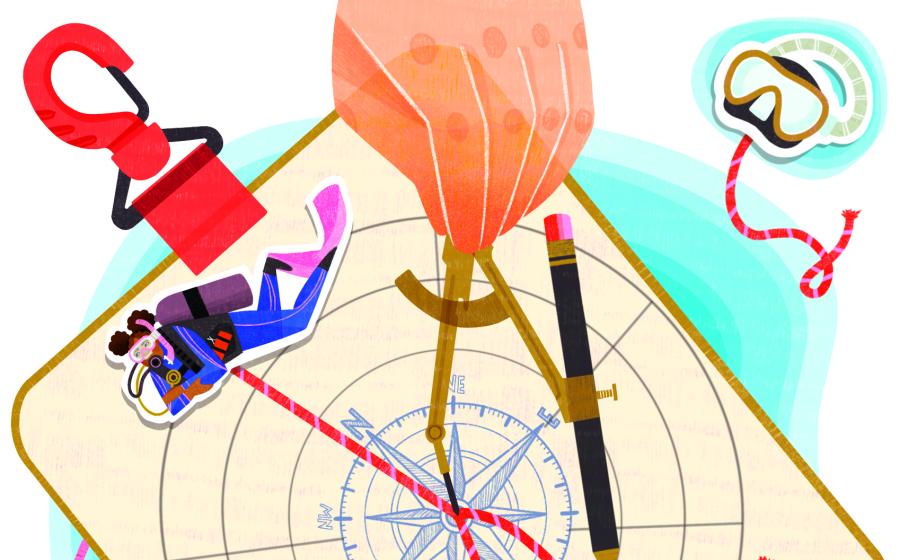

EXTRA: What It Takes to Become a Tampa Police Diver

Interested candidates for the Tampa Police Department Dive Team must meet certain minimum requirements to be considered for training. They must have completed at least 2 years on the job and have a clean departmental record and prior open-water certification. During a three-day intensive tryout/weed-out period, fitness levels are evaluated and water-skills tests include a 50-yard underwater swim on one breath. If accepted for training, novices will practice basic scuba skills, standard search patterns and techniques, rapid helo deployment and hull searches during a one-week course.

One of the more interesting pool sessions requires a prospective diver to start an underwater problem-solving exercise with nothing but a charged scuba cylinder — no mask, fins, regulator or security blanket, just the one essential a human needs to survive underwater: air. Solve a problem and you choose an item from the proffered luxuries. Keep solving problems and you can exit the pool looking like a dive-catalog cover model.

A full roster for the Tampa PD team totals 12 divers including team leader Sgt. Giguere. Numbers vary as a result of promotions, transfers, retirements and large gators. Scheduled monthly practice dives allow for further training and introduction of new equipment and techniques. Actual working details average about four to five per month and provide on-the-job training for new divers paired-up with experienced partners. Check a map of the Tampa area and you’ll appreciate the variety of possible dive sites available.

“Gear up guys, we’re almost on ’em.”

The call from a crewmember on the Hatteras 54 stirred Carl Giguere and Louis Vazquez from their racks. As they pulled on dive skins and checked their small, lightweight SCBAs (composite-material Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus designed for firefighting) modified for SCUBA, they agreed that the night’s activities were a departure from “same-old, same-old.”

Once on deck, they assessed their situation. A Coast Guard cutter stood off from a large ocean-going freighter, which obscured much of the dark horizon on the Gulf of Mexico. Cutter spotlights and the freighter’s own deck lighting made a stark image against the backdrop of black water and night sky. Crew from one of the cutter’s boats threw long shadows as they climbed onto the freighter per their boarding protocol. The Hatteras slid through the water toward the freighter’s stern.

Hidden Cargo

A few hours earlier, Giguere and Vazquez had boarded the Hatteras in Tampa, Florida, at the request of U.S. Customs agents who had an interest in the foreign-flagged freighter; the night’s party would be jointly hosted by U.S. Customs, U.S. Coast Guard and the Tampa PD Dive Team.

The predive briefing by customs covered what the divers needed to know for their part. Customs had credible information that the target vessel was carrying a large quantity of marijuana in its rudder compartment, and they were interested in determining its final destination. Whether the captain or crew of the ship had knowledge of the contraband cargo was unknown.

On large ships, the area where the rudderpost enters the stern of the ship is housed in a small compartment accessible by water from underneath the hull. Smugglers will also utilize sea chests, openings in a ship’s hull used for cooling intakes and covered by a removable grate. Ships in port or at anchor sometimes take on cargo in these compartments, which is not listed on the manifest. Delivery of contraband can be made by boat if the ship isn’t loaded, or by divers if the ship is sitting low and access from outside the hull is submerged. Depending on the value of the shipment or the whims of the shipper, chaperones may also stow away in the compartment as investment security consultants. Accommodations are less than luxurious.

The Dive

Giguere and Vazquez slid into the warm Gulf waters and faced a surface swim of several hundred feet. Under the looming swell of the stern they submerged and located their access point after a brief search. Surfacing in the compartment, their lights picked out a web of ropes crisscrossing the opening and bales of marijuana wrapped in dark plastic on the ledges above the ropes.

Now their job was to attach a small, inconspicuous transmitter to one of the bales. A thin wire running from the transmitter was designed to part if the bale was moved and caused the transmitter to begin announcing its location to monitors. The smaller size and lighter weight of the modified SCBA setup paid off as they completed their task in crowded quarters.

With the transmitter in place, they reversed their route and dropped back through the access and resurfaced in the Gulf for the swim back to the Hatteras. Total time from splash to recovery was about one hour. With the divers back aboard the Hatteras, the Coast Guard boarding crew returned to their cutter and the three vessels departed the rendezvous on divergent courses.

**Useful Intelligence **

Giguere and Vazquez never learned the outcome of the exercise. If crew aboard the freighter knew of the marijuana it’s possible they were aware of the divers’ activities and tipped off those assigned to remove it from the compartment. No attempts to retrieve it were made while the ship was in Tampa and under surveillance. But even forcing the smugglers to change routine may provide useful intelligence.

It’s not uncommon for outside agencies to request the services of police dive teams. Organizations with infrequent need for underwater investigative services tend to contact local police for dive services provided by well-trained divers who are also aware of evidence collection and chain-of-evidence procedures. Post 9/11 concerns have ramped up the need for divers trained in vessel searches, underwater structure security and explosive ordnance recognition and disposal (EOD). Larger departments such as Tampa PD and county and state units will usually provide dive services to departments with limited resources upon request, and to most of the divers attached to part-time dive units a bad day diving is a good day at work.

_Charles “Chuck” Ford was scuba certified in 1974 in Monterey, CA, while stationed with the U.S. Navy. A retired member of the N.Y. State Police, he served on the Troop D Dive Team for 18 years, several of those years as Troop D Senior Diver.

_

EXTRA: What It Takes to Become a Tampa Police Diver

Interested candidates for the Tampa Police Department Dive Team must meet certain minimum requirements to be considered for training. They must have completed at least 2 years on the job and have a clean departmental record and prior open-water certification. During a three-day intensive tryout/weed-out period, fitness levels are evaluated and water-skills tests include a 50-yard underwater swim on one breath. If accepted for training, novices will practice basic scuba skills, standard search patterns and techniques, rapid helo deployment and hull searches during a one-week course.

One of the more interesting pool sessions requires a prospective diver to start an underwater problem-solving exercise with nothing but a charged scuba cylinder — no mask, fins, regulator or security blanket, just the one essential a human needs to survive underwater: air. Solve a problem and you choose an item from the proffered luxuries. Keep solving problems and you can exit the pool looking like a dive-catalog cover model.

A full roster for the Tampa PD team totals 12 divers including team leader Sgt. Giguere. Numbers vary as a result of promotions, transfers, retirements and large gators. Scheduled monthly practice dives allow for further training and introduction of new equipment and techniques. Actual working details average about four to five per month and provide on-the-job training for new divers paired-up with experienced partners. Check a map of the Tampa area and you’ll appreciate the variety of possible dive sites available.