The Future of Diving With Great White Sharks

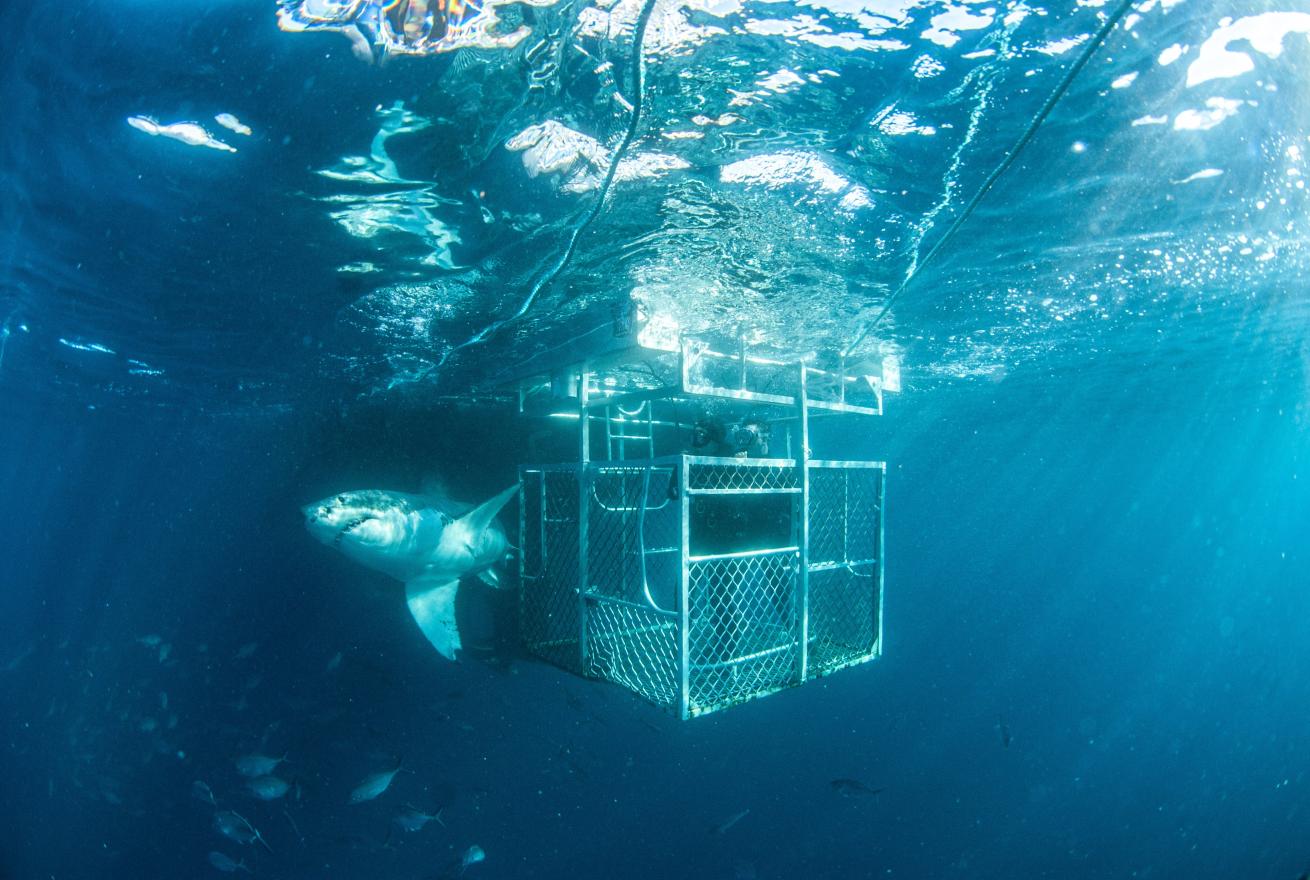

Courtesy Andrew Fox/Rodney Fox Shark ExpeditionsA white shark and scuba diver come face-to-face at the bottom cage in South Australia.

“Here’s Demi—she’s got a beauty spot on her cheek. Carrie has a cute little snub nose. That’s Elvis. He had such a personality—a world-class jumper.”

This isn’t your average family album. I’m sitting with Andrew Fox, a great white shark photographer and researcher, in his Adelaide, South Australia office, flipping through photos of just a few of the hundreds of sharks he’s named, tagged and studied. It’s a calling that runs through his veins. His father is Rodney Fox—a champion spearfisher who miraculously survived a great white bite in 1963 only to dedicate his life to conservation efforts and pioneer shark cage diving.

Today, Fox continues his father’s legacy by running Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions, the only liveaboard that sails to the remote Neptune Islands where the Spencer Gulf meets the Great Australian Bight. A great white hotspot and home to Australia's largest colony of fur seals, the area hosts rugged coves and grassy seabeds that provide an alluring feeding ground for hungry, migrating sharks. It’s also one of the few places where intrepid divers can come face-to-face with the formidable and mysterious predators. And I’ve just flown nearly 11,000 miles to Port Lincoln for the privilege.

Courtesy Andrew Fox/Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions“The Rodney Fox” cruises through the Neptune Islands in South Australia.

I am far from the only one willing to make the arduous journey. Since Rodney welcomed his first cage diving clients in the 1970s, the shark tourism industry has boomed worldwide. It’s estimated that within the next 20 years, shark diving will begin to generate more than $780 million per year globally, with 71% of all divers willing to pay more to observe sharks than any other species.

Related Reading: How to Photograph Pelagic Sharks

In South Australia alone, great white diving contributes an estimated $11.3 million to the economy. Still, many divers, concerned about the effects they might have on the animals’ natural behavior, well-being and human safety, decline to take part in baited dives.

The Closure of Isla Guadalupe

In 2023, this debate came to a head with the high-profile closure of Mexico’s Isla Guadalupe, a popular white shark diving site and biosphere reserve. The government enacted a total ban on “all tourism activities, and film and TV productions,” citing bad practices that put sharks and tourists at risk, including swimming outside cages, mishandling bait and dumping pollutants.

Mauricio Hoyos, a shark expert who has researched Guadalupe’s great white (Carcharodon carcharias) population since 2004 and helped create the island’s cage diving code of conduct, warned tour operators about the need to develop and enforce strict regulations in the local industry. He found the number of cage diving liveaboards nearly doubled from 2014 to 2019, without consideration of the impact on the species.

Photo credit: Alexandra Owens.A curious white shark makes a close pass by Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions’ bottom cage—and the author’s camera.

Two horrifying incidents soon sealed the island’s fate: In 2016, a shark sustained serious injuries while trying to free itself from the bars of a cage and a similar event in 2019 likely resulted in the death of another shark.

“More juvenile sharks come to Guadalupe when warm waters move south during a marine heatwave called ‘The Blob,'” says Hoyos.

“It’s an issue because the cages are designed for adults; the space between the bars is 75 centimeters. Unfortunately, a juvenile shark fits perfectly in this opening. They cannot swim in reverse [if they accidentally run into the cage]. They’re scared, so sometimes they twist hard to get out and injure their gills, which is a very vascularized part of the body.”

Nevertheless, Hoyos—like much of the international diving community—was shocked by the announcement that Guadalupe was shutting down without warning or a chance to correct course further. Now, as I listen to the first briefing of my five-day expedition in South Australia, I am eager to look deep into the cobalt blue eyes of a great white but I just can’t shake Guadalupe from my mind. Is it really possible to run a cage diving business that isn’t at the expense of sharks?

Courtesy Andrew Fox/Rodney Fox Shark ExpeditionsA white shark pays a visit to the surface cage.

The Australian Response to Cage Diving Concerns

South Australia faced a similar though much less dramatic turning point in the late 2000s, when great whites (and divers hoping for a glimpse of them) increased at the Neptune Islands, which was a worry to local surfers and abalone divers. Rather than closing the cage diving operations, the State Government stepped in with a solution: South Australia's White Shark Tour Licensing Policy, which restricted the ways that you can attract sharks, limited cage diving licenses and equipped the Neptunes with a monitoring program and adaptable management framework.

According to a study of 20 years of data collected by tour operators and eight years of acoustic tagging, the new policy has been a clear success. White shark residency returned to and has remained at baseline levels since 2013.

“Any human activity has the potential to affect animals and natural resources if unmanaged,” says Charlie Huveneers, associate professor, director of Flinders University Marine and Coastal Research Consortium and leader of the Southern Shark Ecology Group. “Our studies show that the cage diving industry has minimal impact on white sharks and the Neptune Islands Group Marine Park where it takes place.”

Alexandra OwensThe Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions team drags the bait line toward the surface cage, attracting the attention of a white shark.

Caged 60 Feet Below

As we pull up to the North Neptunes, the chumming (known as burley in Australia) begins. Here, the recipe is frozen bluefin tuna byproduct purchased from Port Lincoln’s many fisheries—a tuna gut popsicle, if you will.

The Rodney Fox handlers use the smell of this fatty oil to lure the sharks near the boat. Rancid tuna gills, entrails and heads provide a tempting visual target and are tied onto a hemp line that naturally degrades without injuring the shark’s mouth.

Anticipation hangs in the air along with the putrid smell of rot. Many of us have come a long way—from Scotland, France, the United States—and while the Neptunes are famous for their reliable great white sightings, it’s never a guarantee.

We haven’t spotted anything from the surface, but I’m instructed to gear up. Rodney Fox offers the world's only ocean floor great white cage for certified divers, and I’m about to see if the view is better from 60 feet below.

Related Reading: Standout Stay: Glamping and Diving in Western Australia

Courtesy Andrew Fox/Rodney Fox Shark ExpeditionsA juvenile great white approaches the deep cage.

I squeeze myself into two layers of wetsuits, a weighted vest, hood, gloves and booties and waddle over to the bottom cage where I’m lowered at a creeping pace down to the lush seabed. Eagle rays and gummy sharks weave between the swaying grass.

I try to sharpen my eyes, to look deeper into the water column, but they’re met with darkness. Out of nowhere, a nine-foot male white shark parts a school of jack fish and cautiously circles us from a distance, picking up the scent of chum safely stored in a metal box inside the cage.

There’s no urgency, no aggression in his movements. Away from the surface where they most frequently hunt, great whites are peaceful—and at the risk of anthropomorphizing them—shy. Fox tells me I’m not crazy. “We tend to get more engagement in the bottom cage when there are less people in it, because the sharks have less eyes on them.”

I believe it—these are ambush predators, after all. In the ocean’s most thrilling game of peek-a-boo, the great whites only seem to come within arms length of me if I pretend to look in the opposite direction. Most of our dives are spent just quietly admiring this most thrilling example of evolutionary design.

Otherwise on the surface, the sharks are noticeably bolder as they swim back and forth to investigate the cage, bumping it with their sensitive snouts and spy hopping for a better view. Our presence surely disrupts their natural behavior, if only because we distract them from hunting. But it’s nothing like the stories of Guadalupe that I’ve heard through the grapevine, in which handlers could be tipped to intentionally feed sharks or drag the bait line in front of the cage for the perfect “Jaws” photo opp.

Here, kingfish snatch most of the scraps before the great whites even reach the surface. When a shark does outmaneuver a handler and grabs the bait, he quickly spits out his paltry reward and disappears, apparently disgusted by the lack of satisfying fat.

According to Fox, this behavior is common and can actually lead to negative habituation where the sharks show diminishing interest in the bait. He explains that sometimes the team may see the shark’s tag pinging on the receiver, but the show is already over—they’ve learned the juice isn’t worth the squeeze.

“We don’t want to be a rodeo act,” says Fox. “This is a beautiful animal. That’s been my dad’s mission from the start—he never wanted to make a circus out of the sharks. Once you get to know them, you don't want them to bang into the cage. I appreciate he was way ahead of his time. He just wanted people to appreciate their majesty and their power.”

Related Reading: 8 Best Places for Shark Encounters

Courtesy Andrew Fox/Rodney Fox Shark ExpeditionsA white shark swims near the surface at the Neptune Islands.

The Role of Shark Diving in Conservation and Education

Over the course of five days, I begin to recognize some of the great whites by their scars and notched dorsals. Two individuals frequently grace us with their presence: Biteface, named for his prominent, freckle-like wounds from feisty seals, and MacKenzie, who bears an M-shaped marking on her side.

I also notice a few sharks with non-invasive trackers that have been placed by Huveneers to study population trends and behavior patterns. This is just one of many projects that collaborates with the Rodney Fox team, as they regularly work to assist universities, scientists, governments and media with data collection.

One fascinating finding from Huveneers and colleague Vinay Udyawer: White shark residency patterns at the Neptunes are seemingly unaffected by the presence of cage diving operators. While male great whites inhabit the islands year round, females come in greater numbers in austral winter (April to August) when seal pups enter the ocean. Much to the disappointment of cage divers, the sharks also have an unfortunate habit of disappearing for months at a time, perhaps due to the presence of orcas.

However, some experts are cautious to dismiss the idea that baited cage dives don’t affect sharks. "I think it's safe to say that chumming and baiting will condition these animals and habituate them,” says Greg Skomal, a senior scientist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. “But at the end of the day, [cage diving operations] are on the plus side of the ledger in terms of their contribution to education and shark conservation, so I'm a proponent of them as long as they're well-regulated…Many of the scientists I know around the world work with, hire and participate in shark cage diving ecotourism [charters].”

After dinner one night we sit down to a lecture emphasizing the importance of shark conservation efforts. While several divers are visibly moved, I’m most interested in the reactions of non-certified passengers who have encountered sharks for the first time on this trip.

Two teenage brothers from Melbourne tell me that they’re now inspired to get their scuba certification, while Darin Miranda, a financial analyst from Sydney, says he views sharks in a new light. “Every encounter felt special and gave me a sense of fulfillment I never thought I would have,” he reflects. “This experience has made me realize that greater efforts need to be made to conserve sharks as a species. I’ve come to understand that their survival is precarious given the impact people have had on them.”

The Future of Cage Diving in Mexico

Today, the future of the great whites of Guadalupe is uncertain. Some experts, including Hoyos, remain concerned that without the constant presence of cage diving boats, the white sharks may be vulnerable to poachers. The opportunity to gain knowledge from the annual gathering of these great whites—a notoriously elusive species—will also be lost.

But Hoyos says that the recent election of climate scientist and former Mexico City mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, who has a track record of supporting sustainability and conservation initiatives, fills him with hope that one day the island will reopen. There are already signs that the government is ready to work together, granting Hoyos scientific permits to study white sharks in the Sea of Cortez.

“If you do things properly, [cage diving] is a very good tool for conservation—but also to create awareness and change the perception of these animals,” he says. “When they first arrive, people will ask me, ‘What should we do if a shark attacks the cage? Should I wear a white wetsuit because the black wetsuit makes me look like a seal?’ I see in their eyes they’re excited, but also very scared. But when they come out of the water after just 60 minutes, people are super happy. Some of them are crying. They tell me, ‘This was the best day of my life.’ The image of the white shark has changed completely for thousands of people thanks to cage diving.”