Computer Bug

December 2001

One of the hallmarks of safe technical diving is equipment redundancy. Recreational divers typically have fairly immediate access to the surface. Technical divers do not have this luxury, however, and must be much more self-reliant under water. Applying Murphy's Law to technical diving means that two pieces of equipment for the same job should be treated as having only one piece. And when diving with only one piece of equipment for a job, a diver must plan to complete the dive without that piece of equipment at all. Failure to adhere to this rule can lead to catastrophe.

The Dives

Trevor was an experienced technical diver and instructor in his early 30s. He was making a series of deep-air training dives with two experienced students and completing some individual dives to check equipment configurations. Over the course of several days, Trevor completed three dives to approximately 200 feet and two dives to 150 feet at a North Florida technical diving and training site.

The freshwater dives were all completed using air as a bottom mix and 80 percent nitrox for decompression from 30 feet to the surface. Each diver was equipped with appropriate redundant equipment: twin cylinders with isolation manifolds, dual bottom regulators, individual tanks of decompression gas and staged decompression gas for emergencies. Divers were using either two computers or a computer with a depth gauge, timer and tables for backup. Trevor not only had two computers, but also tables with watch and depth gauge for backup.

All dives were completed without incident. In addition to the training dives, Trevor also completed a solo dive for equipment checks on day two and a solo dive to retrieve safety equipment on day three. The divers all maintained proper hydration and rest throughout the weekend, and Trevor required religious adherence to ascent-rate limitations, staged decompression stops and an additional safety stop. Following the dives, the divers completed 30 minutes of surface decompression and began the arduous task of loading the technical equipment for the trip home.

Symptoms and Treatment

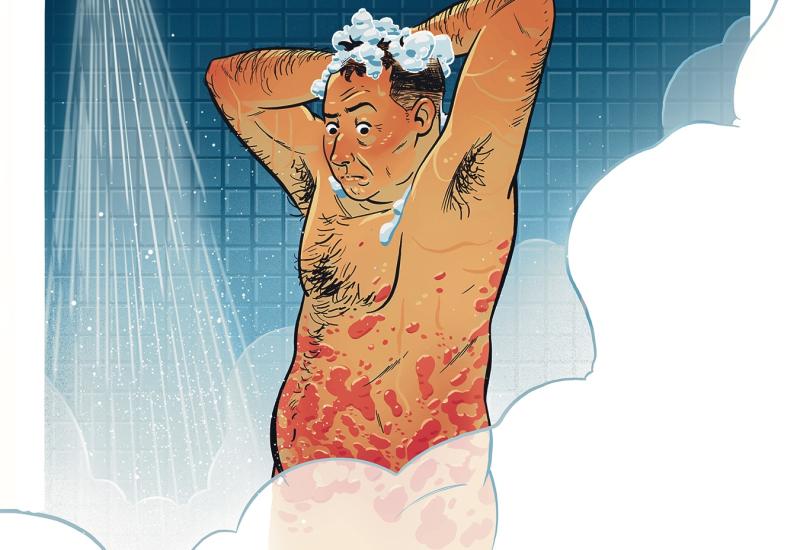

About two-and-a-half hours after the dive, the divers stopped for the traditional post-dive meal. While eating dinner, the instructor suddenly presented symptoms of DCS: extreme and immediate fatigue, numbness in both hands and partial loss of muscle control on the left side of the body. Symptoms were immediately recognized. The instructor placed himself on oxygen, started an IV and was transported immediately to a nearby chamber facility. A quick assessment by emergency room personnel verified field determinations of DCS and the instructor was treated on a Table 6 Navy Hyperbaric Treatment Schedule that resulted in a complete resolution of symptoms.

Analysis

Although the outcome was good, the divers involved in this incident were left with questions about what went wrong. Equipment redundancy was the answer.

Each diver adhered to an individual computer profile based on his or her dive computer for decompression. Trevor was using a state-of-the-art hoseless, gas-integrated computer. The computer had experienced several technical problems and had been returned to the manufacturer for repair a few times. Trevor had just received the computer back from the manufacturer with verification that it had been fully checked and was safe to dive. Unfortunately, the computer was not safe to dive and was providing erroneous depth information on the wrist unit and for decompression profiling. Although Trevor carried two dive computers, one was tucked away as a backup in the event of a system failure on the primary dive computer.

Until the safety stop on the last dive of the series, Trevor had never checked the backup computer. During the last decompression stop, the primary computer stopped providing useful information, and he completed his last stop and a safety stop by using a timer. For added safety, he added 10 minutes at 15 feet on 80 percent nitrox. During this last stop, Trevor checked the backup computer and noted curiously that it was locked in a gauge-only mode. A later comparison of Trevor's computers and the computers of other team members verified that his primary computer had been providing erroneous decompression profiles for at least two of the three previous days.

Lessons for Life

-

For technical diving, redundant equipment must be serviceable and should be checked periodically throughout the dive to ensure its continued function.

-

Electronic equipment, such as computers, may fail without overt signs of failure. Divers are wise to cross-reference computers when using a backup and to follow the recommendations of the more conservative computer.

-

Divers should never use a recently repaired or new piece of equipment on challenging dives until they have been checked thoroughly for function on conservative, shallow-water dives.

-

Never delay seeking treatment when DCS is a possibility. In this incident, immediate response to the presentation of symptoms of DCS resulted in an outstanding outcome.

-

All divers should be trained in oxygen administration, CPR and basic first aid. Fortunately, the divers involved in this incident had proper training and equipment to render immediate first aid at the first signs of pressure-related injury.

December 2001

One of the hallmarks of safe technical diving is equipment redundancy. Recreational divers typically have fairly immediate access to the surface. Technical divers do not have this luxury, however, and must be much more self-reliant under water. Applying Murphy's Law to technical diving means that two pieces of equipment for the same job should be treated as having only one piece. And when diving with only one piece of equipment for a job, a diver must plan to complete the dive without that piece of equipment at all. Failure to adhere to this rule can lead to catastrophe.

The Dives

Trevor was an experienced technical diver and instructor in his early 30s. He was making a series of deep-air training dives with two experienced students and completing some individual dives to check equipment configurations. Over the course of several days, Trevor completed three dives to approximately 200 feet and two dives to 150 feet at a North Florida technical diving and training site.

The freshwater dives were all completed using air as a bottom mix and 80 percent nitrox for decompression from 30 feet to the surface. Each diver was equipped with appropriate redundant equipment: twin cylinders with isolation manifolds, dual bottom regulators, individual tanks of decompression gas and staged decompression gas for emergencies. Divers were using either two computers or a computer with a depth gauge, timer and tables for backup. Trevor not only had two computers, but also tables with watch and depth gauge for backup.

All dives were completed without incident. In addition to the training dives, Trevor also completed a solo dive for equipment checks on day two and a solo dive to retrieve safety equipment on day three. The divers all maintained proper hydration and rest throughout the weekend, and Trevor required religious adherence to ascent-rate limitations, staged decompression stops and an additional safety stop. Following the dives, the divers completed 30 minutes of surface decompression and began the arduous task of loading the technical equipment for the trip home.

Symptoms and Treatment

About two-and-a-half hours after the dive, the divers stopped for the traditional post-dive meal. While eating dinner, the instructor suddenly presented symptoms of DCS: extreme and immediate fatigue, numbness in both hands and partial loss of muscle control on the left side of the body. Symptoms were immediately recognized. The instructor placed himself on oxygen, started an IV and was transported immediately to a nearby chamber facility. A quick assessment by emergency room personnel verified field determinations of DCS and the instructor was treated on a Table 6 Navy Hyperbaric Treatment Schedule that resulted in a complete resolution of symptoms.

Analysis

Although the outcome was good, the divers involved in this incident were left with questions about what went wrong. Equipment redundancy was the answer.

Each diver adhered to an individual computer profile based on his or her dive computer for decompression. Trevor was using a state-of-the-art hoseless, gas-integrated computer. The computer had experienced several technical problems and had been returned to the manufacturer for repair a few times. Trevor had just received the computer back from the manufacturer with verification that it had been fully checked and was safe to dive. Unfortunately, the computer was not safe to dive and was providing erroneous depth information on the wrist unit and for decompression profiling. Although Trevor carried two dive computers, one was tucked away as a backup in the event of a system failure on the primary dive computer.

Until the safety stop on the last dive of the series, Trevor had never checked the backup computer. During the last decompression stop, the primary computer stopped providing useful information, and he completed his last stop and a safety stop by using a timer. For added safety, he added 10 minutes at 15 feet on 80 percent nitrox. During this last stop, Trevor checked the backup computer and noted curiously that it was locked in a gauge-only mode. A later comparison of Trevor's computers and the computers of other team members verified that his primary computer had been providing erroneous decompression profiles for at least two of the three previous days.

Lessons for Life

For technical diving, redundant equipment must be serviceable and should be checked periodically throughout the dive to ensure its continued function.

Electronic equipment, such as computers, may fail without overt signs of failure. Divers are wise to cross-reference computers when using a backup and to follow the recommendations of the more conservative computer.

Divers should never use a recently repaired or new piece of equipment on challenging dives until they have been checked thoroughly for function on conservative, shallow-water dives.

Never delay seeking treatment when DCS is a possibility. In this incident, immediate response to the presentation of symptoms of DCS resulted in an outstanding outcome.

All divers should be trained in oxygen administration, CPR and basic first aid. Fortunately, the divers involved in this incident had proper training and equipment to render immediate first aid at the first signs of pressure-related injury.