Understanding the Bahamas' Underwater Cave System

Kewin LorenzenMany caves in the Bahamas have entrances called "blue holes" where the cave ceiling has collapsed, creating a sinkhole large enough to enter.

On a sticky Thursday morning, a garish turquoise van rumbles down the empty streets of Freeport, Grand Bahama. It’s bound for a makeshift dive locker in an old house where Cristina Zenato and her husband, Kewin Lorenzen, prepare for their cave dives. Once inside, they pore over a map of the Old Freetown cave system—a sprawling, 23,400-foot (4.4-mile) network of submerged tunnels snaking through limestone bedrock nearly 3 miles thick beneath their feet. Zenato and Lorenzen have mapped every accessible inch of the system. The rest remains uncharted territory behind tight passages and collapsed areas where divers cannot pass.

Kewin LorenzenBlue holes tucked into the forest are dramatic entrances to the Bahamas underground.

Zenato, a pioneering cave explorer, views these hidden spaces as more than just natural wonders—they’re misunderstood treasures to be protected. “If there’s one place on this planet that suffers from out of sight, out of mind, it’s flooded caves,” she says. Her work, mapping these underwater labyrinths, reveals how water moves through the earth, supports life and preserves geological and biological history.

Cave Diver’s Playground

Every cave dive begins with exhaustive planning. Zenato knows the Old Freetown system so well she could likely navigate it with her eyes closed. Yet, she still approaches each technical excursion with meticulous planning, detailed checklists and thorough mental and physical preparation, no matter how familiar she is with the site.

With tanks and gear loaded, the turquoise van peels away from the dive locker and onto the pavement. Eventually, it stops on an unmarked dirt road at the entrance to the pine forest. No one else will be coming this way any time soon. The team unloads tanks, cameras, drysuits and rebreathers under a tent hastily set up to shield them from the relentless Caribbean sun.

Kewin LorenzenThe dive team carries gear through the pine forest to reach the cave's entrance.

A short trek over fallen leaves leads to the dive site—a hole the size of a small swimming pool obscured by muddy water, tree branches and debris that must be pushed aside to enter. These “blue holes,” as they’re called, appear like secret doorways in the forest and act as portals to the underground.

Gear is meticulously set up, checked and checked again before the divers submerge, slipping silently through a crack in the rocks where red, tannin-stained water signals the transition from light to darkness.

Kewin LorenzenThe author (left) and Zenato don their gear in a shallow pool outside the entrance to the cave.

Caves are found around the world, but caves in the Bahamas are legendary. On Abaco, a Bahamian island about 100 miles east of Grand Bahama, crystalline caves feature glass-like rods protruding from the ceiling and floor that are so delicate that one errant kick of the fin could topple thousands of years of accumulation. On Grand Bahama, the cave decorations are sturdier, resembling glowing salt lamps under a diver’s torch.

Adding to their intrigue, many caves in the Bahamas connect to the ocean. The water inside is composed of two layers: a freshwater lens pooled from the rain, and a denser saltwater layer below that seeps in from the ocean.

Related Reading: Discovering the Wonders of Mexico's Cenotes for the First Time

As the dive team descends further into the darkness, their torches provide the only source of light in a world that is seemingly closing in on them. They sink down into the shimmering halocline, a swirling salinity boundary where the fresh- and saltwater layers meet. Their vision is momentarily blurred by the convergence of different densities, but below the halocline, visibility opens up to become endless.

The divers’ powerful lights reveal a subterranean museum millions of years in the making.

Kewin LorenzenZenato shines her light behind a large stalagmite so that it glows like a salt lamp.

The Making of Underwater Caves

Some caves form through “dissolution”—rainwater picks up carbon dioxide from the air and soil, becoming slightly acidic. Like a cavity boring through a tooth, this acidic solution eats away at limestone bedrock, creating fractures that enlarge into vast tunnel networks over time.

When caves are dry—such as when sea levels drop during ice ages—mineral-laden water percolates through the limestone ceiling and drips onto the floor, creating icicle-shaped calcium deposits: stalagmites and stalactites. During the last ice age, sea levels were about 300 feet lower than they are now. When the climate warmed and the ice melted, rising seas flooded the caves, creating the highly ornamental 3D museum that Zenato and other cave-certified divers now explore.

Kewin LorenzenTwo cave divers pass through the distorting halocline to enter a cave on Grand Bahama.

Go With the Flow

Caves are more than just archives of history. They are vital sources of fresh water and critical ecosystems that sustain life above and below ground. Dr. Tom Iliffe, a marine biologist based in Texas, has studied cave-dwelling animals for nearly 40 years. Because of their highly biodiverse status, the Bahamas caves have drawn him back time and again for research and discovery. Their inky black depths house fossilized remains of ancient corals and animals, and eyeless critters (mostly crustaceans) inhabit the darkness, providing clues about the evolution of life forms on our planet. “These organisms are distinct and unique, and oftentimes found only in the single cave and nowhere else in the world,” Iliffe says. “Once organisms get into the caves and have adapted there, they’ve lost their eyes and their pigmentation. They do very well living in the caves, but they don’t survive outside of them.”

Like Zenato, Iliffe seeks to impress upon others how special these cave systems are. His research focuses on the discovery of new life forms, while Zenato has found her calling exploring and mapping the twists and turns of places that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Related Reading: Introduction to Cave Diving: What It Takes to Get Cave Certified

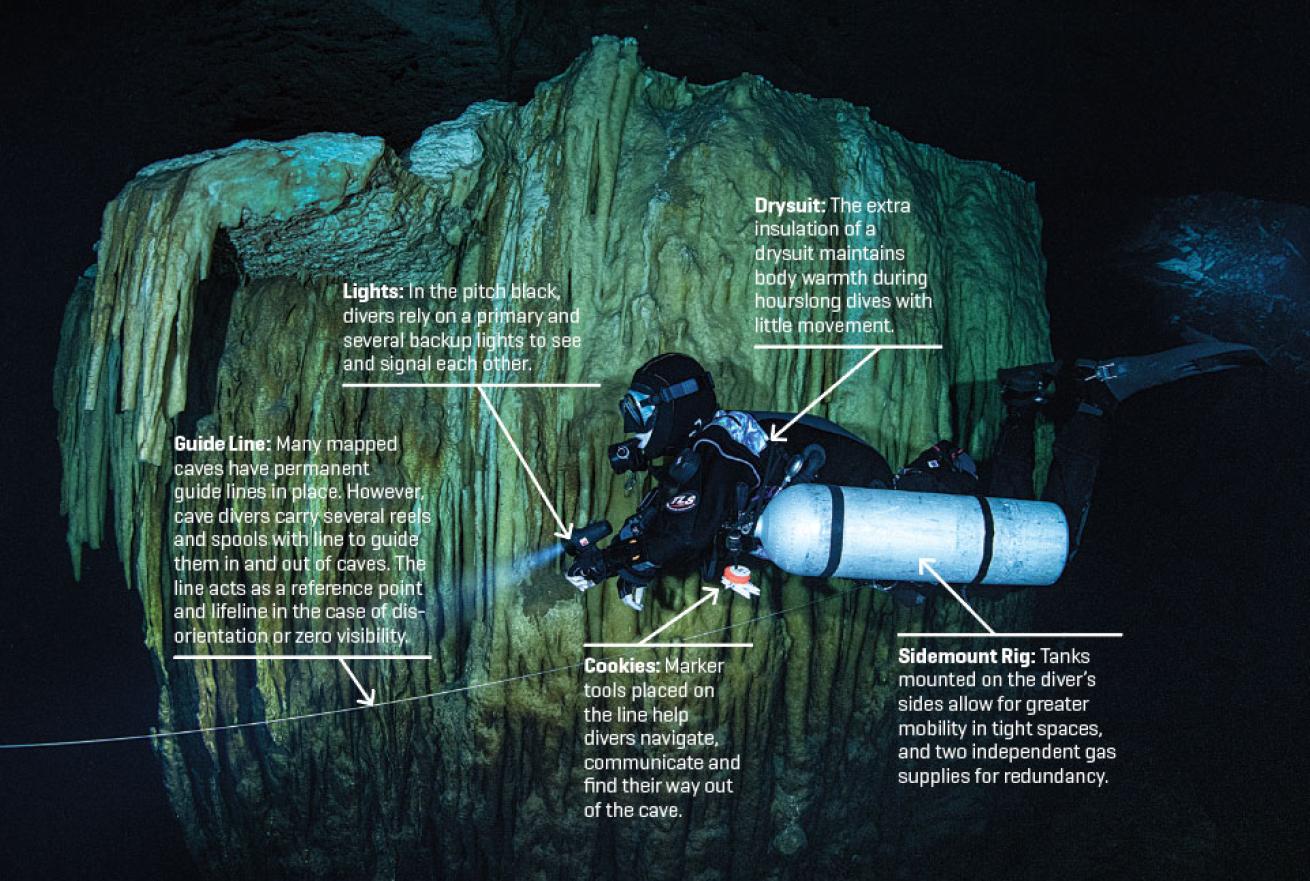

Kewin LorenzenSpecialized gear and redundant life support systems are used when entering any overhead environment.

More Than a Map

Why map caves most people will never see? Because, Zenato explains, “Knowing where the cave is underneath our feet allows us to manage the land above the caves in a more controlled manner.” Many Bahamian caves are linked directly to the ocean, which Zenato demonstrated when she dived into an inland cave and navigated its underwater passages to emerge 500 feet offshore in the sea, a feat verified by two witnesses. This was more than a flashy stunt—it highlighted the critical connection between freshwater and saltwater systems through rivers that flow beneath the forest floor.

Kewin LorenzenCalcium deposits called stalagmites and stalactites are formed when water percolates through the cave's limestone ceiling and drips onto the floor.

Caves that reach the ocean are “literally the circulatory system of the ecosystem,” Zenato says. As the tides move in and out, the water is pushed and pulled through these underground systems, transporting nutrients—and pollutants—between forest, cave, mangrove and coral reef ecosystems. “Anything that’s floating by in the ocean can get sucked down and carried into the caves by strong water currents,” Iliffe says. But the water flows both ways: Any pollutants dumped in the caves can end up in the ocean as well.

These pollutants—fertilizers, heavy metals, sewage, diesel fuel and plastics—come from human activities and land development and damage the integrity of any ecosystem they touch. “This accumulation [of pollutants] leads to loss of dissolved oxygen in the water,” Iliffe says. “So basically, you’re suffocating the animals that are living in the caves.”

Kewin LorenzenA juvenile shark swims in the shallows near shore, where mangroves provide habitat and protection.

Kewin LorenzenThe author (right) and Zenato admire beautiful and delicate cave decorations that have accumulated over hundreds of years.

The downstream effects of pollution reach beyond cave critters and travel throughout the ecosystem. Mangroves—the leggy trees that grow along the boundaries of land and ocean—coral reefs, and the animals that rely on these habitats to survive, from reef fish to sharks, are also affected in ways that are still being studied.

By charting caves, divers can help policymakers better understand how pollutants travel through underground networks, ripple through the food chain, and harm everything from tiny crustaceans to majestic sharks. This knowledge helps identify vulnerable areas, prevent harmful development, and safeguard the health of the interconnected ecosystems that depend on these caves.

In 2015, Zenato and Lorenzen’s mapping efforts accomplished exactly that. Their advocacy led to the expansion of Lucayan National Park to encompass entire cave systems, not just their entrances. This was a step forward in ensuring these hidden treasures are not only mapped and understood but preserved so they can continue to inspire awe and sustain life for years to come.

Related Reading: Entering the Underworld: Cavern Diving in Grand Bahama

Kewin LorenzenZenato’s artistic representation of trash polluting the ecosystem.

Onward and Outward

The divers sip their final breaths underwater as they travel back along the winding passages. A guide line leads them, like a trail of breadcrumbs, back to their starting point. They unclip tanks, scramble out of the mucky pool and trod through the dense Bahamian forest, hauling their gear on tired shoulders back to the van. The divers are alone in the forest. The sounds of flying insects and crunching leaves underfoot the only soundtrack. These caves see few visitors, and each dive is a stride forward in the understanding of countless mysterious passageways.

Zenato’s mission to protect the places she loves is accomplished one step at a time, in what amounts to one continuous project throughout a lifetime. “Every little bit we do every day is part of the bigger picture. Every day I spend with the sharks, and then go map the caves, and then do an educational talk… is part of that bigger picture: How do you understand the interconnectivity of water? What brings the world together?” Zenato says. “In general, I am hopeful. I think there is good in the world. There’s good in us. It’s just a matter of fostering it.”

Note: Cave diving is highly dangerous without proper training and gear. Unprepared entry risks disorientation, equipment failure or fatal accidents. Get trained, use the right equipment and dive with an experienced buddy. Interested in overhead? Check out PADI Sidemount Rec Diver and PADI Cavern Diver training to get started.