Why You Should Never Skip Freediving Safety Protocols

ILLUSTRATION: STEVEN P. HUGHES

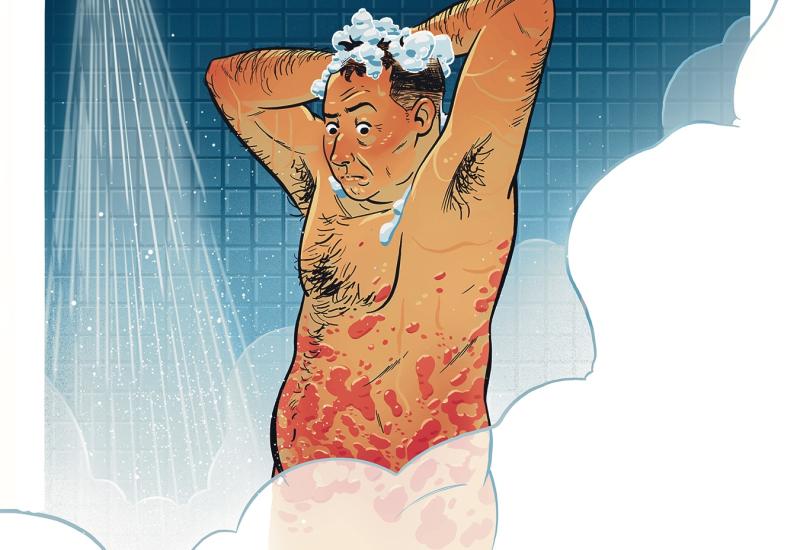

He knew he didn’t make the deepest freedive, but Todd thought he could do better next time. As he neared the surface, Todd felt a little woozy but wasn’t worried. He made it to the surface, but he was already passing out. He immediately began to sink. Then everything went dark.

The Diver

Todd was a 19-year-old male. He was comfortable in the water and an avid freediver. He also loved to spearfish. He was fit and had no known medical conditions.

The Dive

Todd was out spearfi shing with a group of friends on a clear and calm day. As they finished up, the young men went back and forth, playfully discussing who could make the deepest and longest dive. They became competitive and decided to make a dive together to settle the bet. The ocean bottom was 100 feet below them.

The Incident

Each diver took several deep breaths in short succession before descending. They stayed down as long as they could, pushing their personal limits so that they could win the bet.

As soon as Todd broke the surface at the end of the dive, he went limp and began to sink. Two of Todd’s buddies did their best to chase Todd down, but it took them a minute to catch their breath first. They were eventually able to catch him and bring him to the surface, but Todd never regained consciousness.

Related Reading: How Important Is Your Dive Medical Questionnaire?

Analysis

The main issue at play here is how the freedivers prepared for their deep dives. To get ready for the contest, each diver hyperventilated several times.

Hyperventilation, or taking deep, rapid breaths before a dive, reduces carbon dioxide levels in the body. Carbon dioxide in the body triggers the urge to breathe. When it builds up, the urge becomes overwhelming.

It is possible to lower CO2 levels so far by hyperventilating that the body is deprived of oxygen (becomes hypoxic) before the urge to breathe takes place. At depth, pressure on a freediver’s body counteracts falling oxygen levels, allowing you to continue to function normally.

It’s only when the diver nears the surface, and the ambient pressure drops off quickly, that they can lose consciousness. This is known as hypoxia of ascent or, more commonly, shallow water blackout. It happens quickly in the last few feet and can even happen once the diver reaches the surface.

Todd was able to reach the surface, but by that time, he was losing consciousness. A properly weighted freediver will be positively buoyant at the surface. If they lose consciousness on ascent, any air in their lungs is unintentionally exhaled, but they will still float. We know Todd was overweighted because he began to sink with no air in his lungs.

The second factor in this fatal accident was a lack of support. A standby diver should have remained on the surface, geared-up and ready to descend in case someone had trouble. Even better, that standby diver would have descended to 15 or 20 feet to meet the others and help if the divers began having trouble as they neared the surface.

Hyperventilation, or taking deep, rapid breaths before a dive, reduces carbon dioxide levels in the body. Carbon dioxide in the body triggers the urge to breathe. When it builds up, the urge becomes overwhelming.

As it happened, the only divers present to rescue Todd were tired and out of breath. They were able to pull themselves together quickly, but it still wasn’t fast enough. Todd likely inhaled (aspirated) seawater into his lungs as he descended. It probably only took the rescuers two or three minutes to catch up to Todd and bring him back to the surface, but that was enough time for him to drown. Even with lifesaving first aid, Todd never recovered.

When you hyperventilate, there is no way to know how much is too much, especially as depths get deeper or when spearfishing requires chasing or struggling with a big catch. If work is increased due to conditions or the goals of the dive, you should dive more conservatively.

Freedivers should always use a oneup, one-down scenario, so a rescuer is always on the surface and ready to go. Divers should work out a safety plan before the diving begins and stick to it the entire time they’re in the water.

Related Reading: Facing Fear With Jill Heinerth: Focus On Breathing

The PADI Rescue Diver course teaches that when you discover an unconscious diver in the water, you should protect his or her airway. Get the diver’s face out of the water and shield it from waves or splash. Get the diver positively buoyant. Then you have a decision to make. The diver will need for you to breathe for them and deliver chest compressions as well to maintain circulation.

If you’ve been trained, you can deliver rescue breaths as you tow the diver to a stable platform. Depending on the situation, or if the diver needs CPR, you may decide that it will be faster to tow the diver to a place where you can provide more complete care. You don’t want to spend more time than is necessary to get their blood pumping again.

Lessons For Life

Seek training: Take the PADI Freediver course to learn how to dive safely.

Don’t hyperventilate: Relaxation is a far safer and more effective technique to increase breath-hold times.

Dive safely: Always have a safety diver in the water and use one-up, one-down procedures.