Diving the Secret Shipwrecks of Sri Lanka

Simon LorenzSS Perseus

I start my dive day squeezed into a red tuktuk, frantically attempting to keep my gear from sticking out of the window as my driver navigates the tiny three-wheeled open vehicle through the congested streets of Colombo. A wreck diver buddy has told me about the metal haven that lies in front of the Sri Lankan capital, and I’m on my way to the city’s only dive center at Dehiwala Beach to investigate for myself.

Often overlooked for the more colorful reefs, clearer waters and prolific marine life of more popular Indian Ocean destinations such as Indonesia or the Maldives, this area off Colombo on Sri Lanka’s southwestern coast rewards intrepid divers with more than 15 known wrecks and can have warm, crystal-clear water if dived in the right season. Back on the beach, our group of divers together pushes the dive boat into the surf and we zip over to the first wreck site, guided by GPS as permanent buoys cannot be installed here due to the busy port city’s boat traffic. Instead, we drop a small anchor to hook the dive boat to the wreck.

Metal Habitats

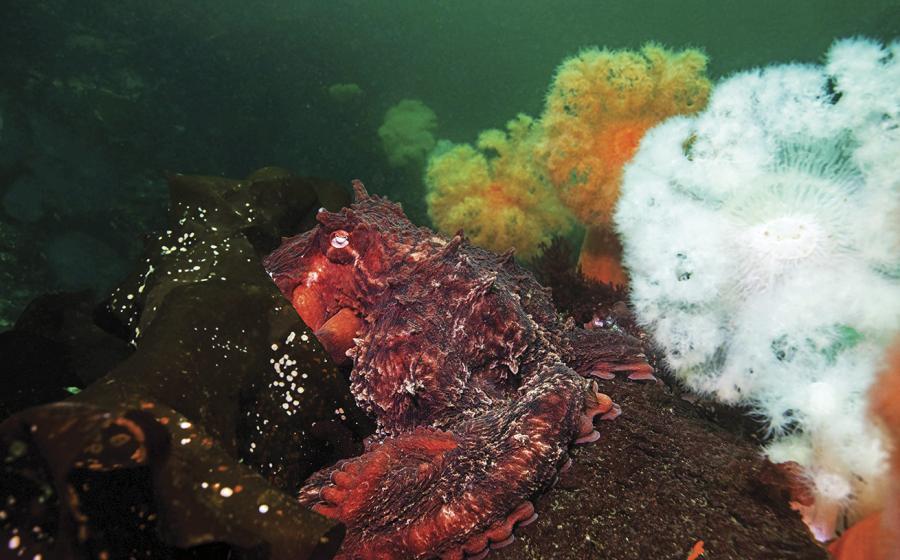

Descending along the line in clear blue water with sun rays dancing around us, we scan below for our first wreck. At first, we can only see a giant ball of fish on the sandy sea bottom. The schools of yellow-lined snappers, bannerfish and angelfish totally engulf the roughly 100-foot Lotus Barge, which rests at about 95 feet. It sits upright on the bottom, so we easily explore the bow, stern and prop and what is left of the structure of the ship. A giant honeycomb moray eel protrudes from its cave and eyes us warily while lobsters dance in and out of the artificial reef. Since most of the bay’s seafloor is sandy, all of the wrecks in this area are a magnet for fish life, creating vibrant, colorful habitats.

“Except for a few offshore reefs, all the nearshore reefs around Colombo have been degraded by coastal development and overfishing, but the wrecks provide a unique habitat for marine life and attract large schools of fish” says Nishan Perera, a marine biologist who set up the Island Scuba dive shop a decade ago.

Simon LorenzTrinco Blue

There are several of these wrecked barges along the coastline here. Colombo was an important colonial harbor and is now a busy modern port. Even before colonization, the natural harbor of Colombo was a trading post for the Arab and Indian worlds. For the Portuguese, then Dutch and later the English, it was an important pit stop on the long route to and from Southeast Asia, and later a region for growing Ceylon tea. Over the centuries, many ships sank here due to storms, disuse, abandonment and even wars. Aside from barges, there are several large cargo ships on the seafloor, many with their cargo intact. One ship, loaded with building materials and called Medhufaru, is just below the surface with its entire structure fully intact. The superstructure offers nice penetration options to explore the big galley and the bridge, where you can still see old-school computers, a printer and air conditioners.

Simon LorenzCoal Ship

A bit deeper lies the Pecheur Breton, lying on its side at 105 feet with fully collapsed cargo floors creating two huge swim-through tunnels that act as refuge for schools of fish. There is much marine life and coral growth on the ship. Its masts are still intact and point into the blue abyss, and the seafloor is littered with lifeboats.

Simon LorenzCountless fish cloud and swarm around the wreck of the Lotus Barge, which provides shelter on the otherwise sandy bottom off Colombo.

Car Wreck

The much older car carrier Chief Dragon was loaded with automobiles and car parts that today are littered across the deck and seafloor. The wreck has collapsed in the center area but both bow and stern are standing upright and act as biodiversity hotspots, with huge schools of fish clouding around corals overgrowing old machinery. Below the mountains of aging steel, the ocean has washed a huge basin around the prop shaft, filled to the brim with yellow blue-line snapper.

In the stern, I venture into a crack above a collapsed deck board and discover a tool room complete with work bench, compressors and a large vice clamp. When I tell the divemasters about this later, they are surprised, as they had never noticed this room. The deck floors must have recently collapsed, opening up this entry point. As these wrecks are exposed to strong ocean currents every day they degrade and collapse, creating interesting reefs but also new opportunities for exploration in real time. And few people dive them, so discoveries happen gradually.

Simon LorenzThe lookout tower of the car carrier Chief Dragon rests on the seafloor.

The Sierra

The newest and most unusual dive site off Colombo is the Thermopylae Sierra, aka the Sierra. Like many of the other cargo ships, the Sierra was abandoned at anchor for several years before it finally sank in a heavy 2012 monsoon, fully loaded with building materials and steel tubes. The seafloor bottom here is just 78 feet—lower than the actual height of the ship—leaving the ship’s cargo posts exposed above the waterline.

The entire ship is clouded with reef fish as we approach the bow. Snappers school around the fore posts. The man-made machinery is preserved exquisitely, making the whole experience feel like diving in a huge aquarium. There are exciting penetration points possible, such as the big galley and engine room, and even the steel tubes for ambitious sidemount divers. The superstructure allows for penetration on various floors, but in the higher floors the surge pushes divers to and fro, and loosely swaying wall boards hint that more floors could collapse soon.

Simon LorenzThe Thermopylae Sierra has not been underwater long, but the wreck is already home to endless schools of fish.

The shipwreck is now being investigated to be salvaged for scrap on the pretext of being hazardous to merchant shipping, but the local dive community is fighting to keep it sunk with Facebook groups and petitions. The argument against salvaging the wreck is its marine life. Although Sri Lanka is a hotspot for marine life, the reefs often have poor visibility as most reefs are located close to the shore and suffer from pollution and increased sedimentation from river runoff. As a result, these reefs are degraded, with low numbers of coral and fish. “As a marine biologist I have dived everywhere in Sri Lanka and I can honestly say the wrecks in front of our capital have some of the best marine life, and offer some of the best recreational diving in the country,” Perera says.

On our dives we did see a lot of wildlife. Aside from schools of fish there were many moray eels, stingrays, huge lionfish and big snappers. It is not quite clear why, but there seem to be absolutely no sharks left in the area and the groupers seem to be top of the food chain. Other regulars include sea turtles. The entire beach ring around the island of Sri Lanka is a nesting ground for six of the world’s seven species of sea turtle. One day during a briefing, a hatchling worked its way out of the sand and crawled toward the ocean. It seemed that a hawksbill turtle had nested right next to the dive shop—in the middle of the city!

Sunken History

Aside from barges and cargo ships, these waters also hold historic wrecks. Instrumental to finding all these wrecks was Dharshana Jayawardena. A software professional by trade, he has dedicated all of his private time in the past 15 years diving all over Sri Lanka to find new wrecks and caves.

Most of the known wrecks in Colombo were located by Jayawardena, who searches for clues among the fishermen. “I talk to the local fishermen regularly and ask for places where they catch more fish or have lost fish nets.” Then he starts combing the area. To find some of the deeper wrecks he got into all measures of tec diving.

His two biggest trophies were the British ships SS Perseus and SS Worcestershire. Both were sunk in World War I by the treacherous sea mines placed by the German commerce raider SMS Wolf, which traveled the oceans and sunk a record 37 ships, including two warships, in one long 451-day journey. Commercial trading vessels were its prime targets.

Simon LorenzWreck explorer Dharshana Jayawardena inspects the propeller of the SS Perseus.

Jayawardena spent many years diving the ships, trying to find proof that these wrecks were in fact the sunken British vessels. “I had already given up hope on finding them. But then I started CCR diving and had more bottom time,” he explains. “So I started searching the ships inch by inch and widening my search patterns, including the debris in and around the ships.”

In 2014, on his 22nd technical dive to the suspected wreck of the SS Worcestershire, which lies at 185 feet, Jayawardena finally found the inscribed ships bell in the general area of the mast when shining his torch under a thick metal sheet. Five years later, he located the bell of the SS Perseus by “visually inspecting every inch of the rubble around the ship.” The bell was buried in the sand quite far away from the main wreck, only revealed by a slight curvature in the sand. Both bells were handed over to the Maritime Archaeology Unit in Galle, and once restored, revealed the names of the ships engraved on their sides.

Simon LorenzThe cargo posts of the Thermopylae Sierra rise above the waterline from the sunken wreck below.

Grand Finale

My dive on the SS Perseus is therefore the highlight of this trip. We descend into the warm blue water, Jayawardena around 30 feet below me. It is not until we pass 65 feet of depth that the wreckage of this 443-foot-long armed merchant ship materializes below us. The Perseus was fully loaded with cargo when it hit the German mine en route to Yokohama, Japan.

Diving with Jayawardena on this historic wreck was a thrilling experience. The huge bow with both anchors lies at 138 feet, and the huge propeller is still fully intact. The ship is surrounded by massive schools of fish. Large mangrove snapper, Napoleon wrasse and trevally patrol the area. The ship is mostly collapsed, leaving its steel beams twisted and ragged sticking out of the wreckage, probably protecting the fish here from nets. Right in the beginning we scare a troupe of giant trevally out of the wreck, while groupers hang out in many of the dark crevices.

The most amusing part of this British cargo ship is the store of bottles that spilled out all over the seafloor. According to my well-informed guide, these are turn-of-the-century Johnnie Walker whiskey bottles. Sadly, they are empty, which is no surprise after more than 100 years at the bottom of the ocean.

We have to do a long decompression on the line because once again Colombo’s only nitrox compressor is out of duty. Waiting for my nitrogen levels to drop, I ponder why almost no one knows of these marvelous wrecks. There are two reasons: During Sri Lanka’s civil war, the harbor was a military zone and closed to the public and therefore recreational diving. The other reason is that the extreme monsoons mean Colombo only has clear water for a few months of the year, so keen divers need to plan well and come at the right time. The secrets these waters hold are well worth the effort.

Simon LorenzTrinoc Pikot Whales

The Whales of Trincomalee

Sri Lanka is home to many whales and dolphins as well as the world’s only known nonmigratory blue whale population. The continental shelf around the island is at just the right depth to provide great feeding grounds for the world’s largest marine mammal species. While other populations migrate to colder waters to find food, these whales stay put year-round. Sperm whales can sometimes be seen in super pods, and pilot whales and dolphins often cruise close to snorkel boats. All species are safely protected by Sri Lanka’s anti-whaling laws.

In spring the blue whales can be found in two hotspots: the classic whale mecca Mirissa, or Trincomalee, a lesser-known gathering place.

In Mirissa there is a large fleet of whale-watching boats competing for whale time. The insider tip is Trincomalee, with its small and select approach to whale-watching. There are just a few operators here, and the permits to get in the water are very pricey, keeping boat numbers limited. Looking for whales is an activity for patient people. The boats fan out over the endless blue ocean, often until land has fully disappeared from sight. Scouring the waters, they stay in touch by radio until one boat strikes gold and finds whales. The days out on the rocking boats are long and exposed to endless sunshine, but the occasional rewards are well worth it.

Simon LorenzTrinco Whale

Swimming with the world’s largest animal is challenging. These whales only come up for two to three breaths at a time, in between which the whales swim at a “shallow” 30 to 100 feet of depth. The intervals between breaths are short, and location and timing vary by giant whale-like margins. Good guides, luck, patience and freediving skills are essential to get any interaction time at all. But when a giant blue whale finally gently cruises by like a beautiful gray train with grapefruit-size eyes it is moment that can change one’s life.

When to Travel

The diving season is from November to April, but it’s best from January to March with clear and warm water. This is when the monsoons hit the northern and eastern coasts of Sri Lanka, creating a protected eddy in the southwest. Water temps in spring are around 84-86°F, with 65 to 100 feet of visibility and calm seas.

Simon LorenzIsland Scuba Colombo

There are only two dive shops in the wider area, and Island Scuba is the only dive shop in Colombo itself. Divers should stay in the south side of the city to avoid most of the traffic going to and from the dive shop. The historic Mount Lavinia Hotel, a former British governor residence, is a bizarre and kitschy experience that fits the historic impressions of the diving.

Diving starts early in the morning because afternoons see more swell, making landing the boat on the beach harder. Divers need to be prepared for a day in the blazing sun. Although the boats have some cover, sun protection and water intake are vital.

Dives and hotels are relatively inexpensive in Colombo as everywhere in Sri Lanka. A two-tank dive on the wrecks will cost only $70 USD. But beware technical facilities are limited: At the time of writing the only nitrox compressor in the area was broken.