Dive Training: Frozen with Fear in a Drysuit

Drysuit Diving

The sudden chill surprised Alex when he began his short descent to the shallow bottom. His new drysuit should've been much warmer. He attempted to inflate the suit with the button on his chest, but he couldn't feel the rush of insulating air. The cold continued to spread across his body, and the suit grew tighter around his limbs and chest as his buoyancy decreased and he sank deeper. When he turned to signal his buddy, Alex received another surprise: His buddy was out of sight. Alex knew he had to go up. He struggled to ascend now, forcefully holding down the button on his dry suit valve, but still no air came in, just a sickening, slow trickle of ice-cold water. His breathing accelerated, his air supply dropped and his limbs grew stiff as he drifted toward the bottom.

The Diver

Alex was a relatively new diver with only a handful of dives under his belt. He was in his 30s, in excellent health and showed a lot of enthusiasm for his new sport. He had only dived in a drysuit a few times before, under the supervision of an instructor. This was Alex's first time independently diving dry.

The Dive

Alex geared up with his buddy as they listened to the dive briefing, and then the two entered the water together. At the surface, the water was warmed by the sun to about 70 degrees, but the thermocline was shallow, at about seven or eight feet, and below it, the temperature dropped to the high 30s — definitely drysuit conditions. Visibility was average for the site, about 20 feet. The surface was calm with small, gentle swells, and a mild current was present as they descended toward their target depth of around 25 feet for their shallow dive along a coastal jetty.

The Accident

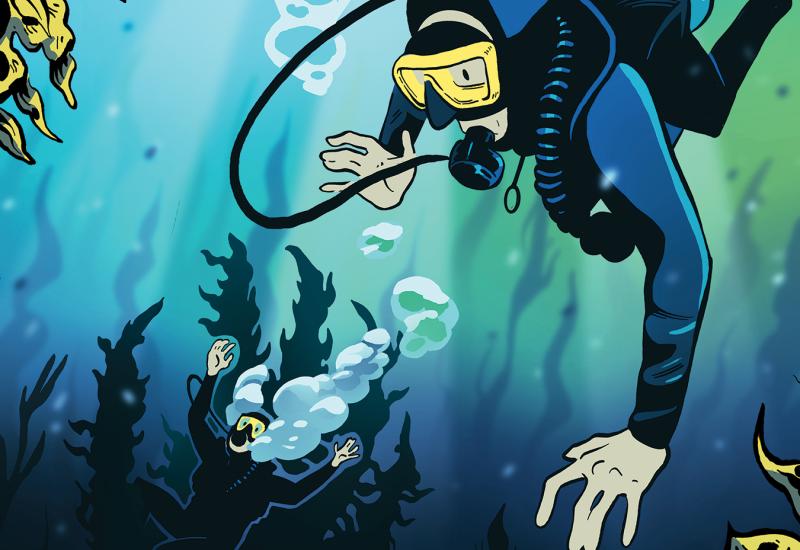

As he descended, Alex noticed the cold and puzzled over his drysuit's inability to keep him warm. He repeatedly pressed the inflate valve, but it took several minutes before he realized no air was entering his suit. In fact, the drysuit's low-pressure inflator hose wasn't even connected. Without the buoyancy from the inflated drysuit, Alex struggled to gain control of his descent. Dealing with these problems distracted him for several minutes, and by the time he turned to ask his buddy for help, he was shocked to find he was all alone. This increased his anxiety even more as he kicked in vain for the surface, but with his drysuit fully compressed next to his body, Alex was extremely negative and unable to ascend. Alex was most likely disoriented and possibly hypothermic by this time, but whatever the reason, he failed to add air to his BC or drop his weights. Alex's dive buddy had ascended within a few minutes of starting the dive, shortly after the two became separated, thinking Alex would meet him at the surface. When Alex didn't come up, a search was rapidly organized, but unfortunately, it was too late. Alex was found drowned on the bottom in only 23 feet of water.

Analysis

The risks of diving in cold water should never be underestimated. In extremely cold water, with temperatures approaching freezing, the impact on the body is immediate. It reduces finger dexterity almost instantly and can impact coordination very rapidly after that. In just a few minutes, without proper protection, the body can become hypothermic. One of the first signs of hypothermia is difficulty focusing and an inability to solve problems rationally. To prepare for dives in these types of conditions, divers should overtrain in more moderate conditions to make every skill and every emergency procedure an effortless second reflex. Alex had not prepared himself to that level, especially with regard to his drysuit.

Even equipment as common as a drysuit requires additional training, additional experience and additional predive safety checks for safe use. Add an extreme diving environment, and these procedures become critically important. A drysuit works by providing an insulating layer of air between the diver and the suit. This space is typically filled with heavy underwear of some sort, but the air space is necessary because the undergarment would be crushed flat next to the diver's body without it and a flat or compressed piece of material has very little insulating power. To inflate a drysuit, a diver has to press a valve button, usually located on the chest of the suit, that's connected to the tank via a low-pressure inflator hose. Like a BC's inflator hose, the drysuit hose connects to the suit valve with a slip-coupling device. Drysuit divers should check this connection and the operation of the valve before entering the water on every dive, and the dry diver's buddy should check the connection and operation of the valve during the predive buddy check. Alex was a new diver with very little drysuit experience, and he apparently missed this vital safety check because the hose was either never connected at all, or it was not connected securely and came undone as he entered the water. This hose can be hooked up underwater. However, this can be awkward, especially in very cold water with heavy gloves or mittens, so it is necessary for drysuit divers to practice this skill in advance. Because drysuits are filled with air, dry divers also tend to wear more weight than wetsuit divers, often distributed across the body, and it is vitally important to be trained in dumping this weight.

Alex apparently failed to practice any of these procedures in advance and as a result, he was unable to respond to the actual emergency when he entered the water. He never inflated his BC, which worked properly upon later inspection, and he never dumped the considerable amount of weight he was wearing. Either of these procedures would have brought him immediately to the surface where his waiting buddy or the other divers at the site could have assisted him.

Lessons For Life

Never underestimate the effect environmental conditions can have on your dive. Extremes of any type will accelerate the effects of any problem, sometimes with disastrous results.

Never use a new piece of equipment on a dive that pushes your comfort zone.

Practice, practice, practice. Rehearse basic diving skills until they become second nature. And pay special attention to emergency procedures — the skills you use least are the ones you should practice most.

Always complete a thorough buddy check before every dive. Check that all hoses are connected and working, note the location of weights and how to ditch them and discuss emergency procedures and the locations of alternate air sources.

Stay with your buddy. Especially in stressful situations, it's vital to keep a frequent check on your buddy's position.

The sudden chill surprised Alex when he began his short descent to the shallow bottom. His new drysuit should've been much warmer. He attempted to inflate the suit with the button on his chest, but he couldn't feel the rush of insulating air. The cold continued to spread across his body, and the suit grew tighter around his limbs and chest as his buoyancy decreased and he sank deeper. When he turned to signal his buddy, Alex received another surprise: His buddy was out of sight. Alex knew he had to go up. He struggled to ascend now, forcefully holding down the button on his dry suit valve, but still no air came in, just a sickening, slow trickle of ice-cold water. His breathing accelerated, his air supply dropped and his limbs grew stiff as he drifted toward the bottom.

The Diver

Alex was a relatively new diver with only a handful of dives under his belt. He was in his 30s, in excellent health and showed a lot of enthusiasm for his new sport. He had only dived in a drysuit a few times before, under the supervision of an instructor. This was Alex's first time independently diving dry.

The Dive

Alex geared up with his buddy as they listened to the dive briefing, and then the two entered the water together. At the surface, the water was warmed by the sun to about 70 degrees, but the thermocline was shallow, at about seven or eight feet, and below it, the temperature dropped to the high 30s — definitely drysuit conditions. Visibility was average for the site, about 20 feet. The surface was calm with small, gentle swells, and a mild current was present as they descended toward their target depth of around 25 feet for their shallow dive along a coastal jetty.

The Accident

As he descended, Alex noticed the cold and puzzled over his drysuit's inability to keep him warm. He repeatedly pressed the inflate valve, but it took several minutes before he realized no air was entering his suit. In fact, the drysuit's low-pressure inflator hose wasn't even connected. Without the buoyancy from the inflated drysuit, Alex struggled to gain control of his descent. Dealing with these problems distracted him for several minutes, and by the time he turned to ask his buddy for help, he was shocked to find he was all alone. This increased his anxiety even more as he kicked in vain for the surface, but with his drysuit fully compressed next to his body, Alex was extremely negative and unable to ascend. Alex was most likely disoriented and possibly hypothermic by this time, but whatever the reason, he failed to add air to his BC or drop his weights. Alex's dive buddy had ascended within a few minutes of starting the dive, shortly after the two became separated, thinking Alex would meet him at the surface. When Alex didn't come up, a search was rapidly organized, but unfortunately, it was too late. Alex was found drowned on the bottom in only 23 feet of water.

Analysis

The risks of diving in cold water should never be underestimated. In extremely cold water, with temperatures approaching freezing, the impact on the body is immediate. It reduces finger dexterity almost instantly and can impact coordination very rapidly after that. In just a few minutes, without proper protection, the body can become hypothermic. One of the first signs of hypothermia is difficulty focusing and an inability to solve problems rationally. To prepare for dives in these types of conditions, divers should overtrain in more moderate conditions to make every skill and every emergency procedure an effortless second reflex. Alex had not prepared himself to that level, especially with regard to his drysuit.

Even equipment as common as a drysuit requires additional training, additional experience and additional predive safety checks for safe use. Add an extreme diving environment, and these procedures become critically important. A drysuit works by providing an insulating layer of air between the diver and the suit. This space is typically filled with heavy underwear of some sort, but the air space is necessary because the undergarment would be crushed flat next to the diver's body without it and a flat or compressed piece of material has very little insulating power. To inflate a drysuit, a diver has to press a valve button, usually located on the chest of the suit, that's connected to the tank via a low-pressure inflator hose. Like a BC's inflator hose, the drysuit hose connects to the suit valve with a slip-coupling device. Drysuit divers should check this connection and the operation of the valve before entering the water on every dive, and the dry diver's buddy should check the connection and operation of the valve during the predive buddy check. Alex was a new diver with very little drysuit experience, and he apparently missed this vital safety check because the hose was either never connected at all, or it was not connected securely and came undone as he entered the water. This hose can be hooked up underwater. However, this can be awkward, especially in very cold water with heavy gloves or mittens, so it is necessary for drysuit divers to practice this skill in advance. Because drysuits are filled with air, dry divers also tend to wear more weight than wetsuit divers, often distributed across the body, and it is vitally important to be trained in dumping this weight.

Alex apparently failed to practice any of these procedures in advance and as a result, he was unable to respond to the actual emergency when he entered the water. He never inflated his BC, which worked properly upon later inspection, and he never dumped the considerable amount of weight he was wearing. Either of these procedures would have brought him immediately to the surface where his waiting buddy or the other divers at the site could have assisted him.

Lessons For Life

Never underestimate the effect environmental conditions can have on your dive. Extremes of any type will accelerate the effects of any problem, sometimes with disastrous results.

Never use a new piece of equipment on a dive that pushes your comfort zone.

Practice, practice, practice. Rehearse basic diving skills until they become second nature. And pay special attention to emergency procedures — the skills you use least are the ones you should practice most.

Always complete a thorough buddy check before every dive. Check that all hoses are connected and working, note the location of weights and how to ditch them and discuss emergency procedures and the locations of alternate air sources.

Stay with your buddy. Especially in stressful situations, it's vital to keep a frequent check on your buddy's position.