Scuba Diving Shipwrecks in the Baltic Sea - Underwater Exploration in Russia

Viktor LyagushkinThe remains of Imperial Russia’s dashing frigate Oleg — a dream target for a team of underwater archaeologists and one determined photographer — proves a nightmare to access in the reality of the Baltic’s stormy black seas.

Jump to More Photos

A tiny dive boat with the military-sounding name RC-311 leaves its St. Petersburg mooring headed for Hogland Island in the middle of the Baltic Sea. On board the 69-foot vessel are a captain, a sailor, a professor, three underwater archaeologists, an underwater photographer and an underwater journalist — me.

To complete any kind of underwater archaeological work in Russia’s Baltic is the definition of success: Underwater research is expensive and requires lots of permits — for the work and for each member of the expedition. Landing a spot on such an expedition is rare; “bums” and “hacks” are usually not taken along. But I am lucky. And worried. I’m afraid I won’t be able to handle it, but it’s my dream to dive on a historic shipwreck. And not just any wreck: Oleg, flagship frigate of the Imperial Russian navy. And Oleg is on our list of anticipated targets.

A majestic sailing battleship of the “screw frigate” type, Oleg sank under very silly circumstances.

In 1869, at a parade in the presence of His Majesty Emperor Alexander II, Oleg accidentally collided with another warship. In just under a quarter of an hour, the pride of the fleet was on an even keel on the seabed at a depth of almost 200 feet, near the island of Hogland, with only the tops of its masts sticking out of the water.

Fortunately, its crew left the ship in an orderly manner and almost no one was lost. Among the few dead were a young soldier who guarded the ship’s safe around the clock. He surely knew the ship was sinking but did not dare to leave his post without orders. Today the frigate Oleg is a paradise for archaeologists, a piece of the 19th century, preserved intact.

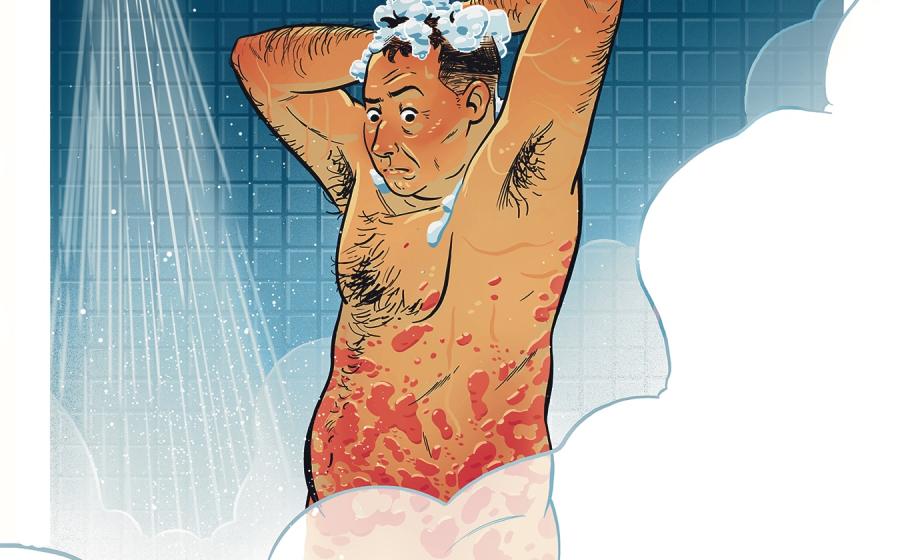

So what was so scary? The Baltic is considered one of the most inhospitable seas in the world for diving; despite having experience with cold water, I will likely have a hard time. You would think anyone would be eager to go, with jewelry and gold piasters just waiting on the sea bottom — if you judge by reports in the press, you might think underwater archaeologists find treasures and vintage champagne every day. Alas.

Those who dive the cold waters of the Baltic are not to be envied. The temperature at the bottom year-round does not exceed 37 degrees F. Visibility is also not a gift; 15 to 25 feet counts as a very good day. A powerful underwater torch looks like a dull yellow speck — mostly divers work by touch. Do they find artifacts? Oh, yes! Household items: bottles, plates and other ceramics. All of that can help in the work of identifying the shipwreck. Only in the movies is it simple — presto! — the hero finds the name on a ship’s board in 3-foot-high brass letters. Usually, a shipwreck lying at the bottom of the Baltic Sea looks like a pile of planks — an incredibly valuable pile of planks, in a cultural and historical sense.

Only the most daring penetrate these wrecks. Hulls are fragile and can fall on the unfortunate archaeologist. Their bowels are covered with a layer of mud — one wrong move and the silt blacks out even pitch-dark water. There’s silt on the ceiling — breathe in and hold your breath, and you might see something. Breathe out, and artificial night falls — and it might not be possible to find your way to the light.

Viktor LyagushkinRussia’s majestic sailing battleship Oleg boasted a double wheel that required two sailors on each side to operate.

Time Travel

Back in the RC-311, photographer Viktor Lyagushkin (my husband) and I have a large cabin, but Vitya’s photo equipment takes most of it. At the bottom of the slippery metal ladder are large transport gas cylinders for diving. The cabin floor is covered with a mess of wires and battery chargers for underwater strobes, and littered with other accessories for underwater photography. The wall over Vitya’s bunk is adorned with felt-tip lines noting the days of our expeditions.

Although it’s typically only a 12-hour trip to Hogland, we reach it in two stages because of a storm, and I am pretty seasick. When we arrive, we hide in a small secluded bay, but that’s just for starters. For three days, the storm does not cease; diving is out of the question. Our team resembles an idling engine, ready to move at any time. The captain sits in the control room listening to weather reports, or works on the diesel engine with his assistant. Archaeologist Igor Galaida cooks in the galley; his colleague Roman Prokhorov, a man with an open smile, conjures over the compressor or tinkers. Viktor fingers his photographic paraphernalia and lights cigarette after cigarette.

Finally, the morning of the fourth day, the weather improves, and everything is in motion. We will dive nowhere but Oleg! We divide into two groups. The archaeologists will inspect the frigate and evaluate its condition. I am assigned to Vitya as his assistant. He explains my tasks at length — what I should do, what we will shoot — then hands me an Ikelite strobe that looks like a blaster from an old space movie, and we begin to assemble our equipment for the dive. Two cylinders on backmount and one on the side; another with oxygen will wait for me under the boat — our dive will be deep and long. With all this on, you feel like an armored tank from World War I, about as heavy and unwieldy.

I jump overboard, holding my mask and regulator. A few kicks and I near the rope leading to the bottom. At about 15 feet, I check my equipment again. Vitya approaches and outlines with his torch: “OK?”

“OK,” I reply. He signals to descend, and we begin to fall along the rope into the darkness.

The deck appears beneath me unexpectedly: Suddenly from the turbidity and darkness comes a huge brass spire, a vertical winch that raised the anchor, to which RC-311 is roped.

I look around, but the water is so murky, I think that we are wasting our time — surely it is not possible to take pictures or investigate the frigate in such conditions. Imagine being in a strange dark room, littered with objects, and you have only a laser pointer. “There,” Vitya signals, and I rush after him, fearing to lose sight of him.

We move from point to point on his order, taking shots; only on the third or fourth stop do I begin to piece together my surroundings. Huge iron cannons wider than an arms’ span still stand on their wooden mountings, ignition fuses scattered beneath them. A two-story command bridge boasts a double steering wheel and a graceful arch to the admiral’s cabin. All completely intact and stunningly real, tangible, isolated from me by only a thin veil of time — I keenly feel how close is that neighboring, ghostly world, where orders are heard and sailors scurry and the wind still sings in the sails of the flying frigate.

While we take pictures, the archaeologists collect artifacts, commissioned by the Kronstadt Maritime Museum. They put them into a special box, then the box goes into a goodie bag. Igor collects while Roman notes on a slate what was found and where. Then the guys wave their hands at us and head inside the ship, into the admiral’s cabin. Descending over the board, suddenly I see huge brass letters: Oleg. I rub them with my gloved hand. The barrier of time feels especially thin, as if only the layer of silt on these letters separates us — flick it away, and you find yourself in another century. Suddenly I hear “Glug-glu-glu-glug-expletive!” and look around. Vitya glares at me, swearing into his regulator. I was daydreaming, forgetting that we are here to make photographs.

Viktor LyagushkinEmerging from a century and a half of silt, Oleg’s anchor capstan is still a thing of beauty.

It seems a short time, but my Shearwater is showing me that we must return. We ascend slowly, with all the stops, the water around us brightening as we rise toward the surface and sunlight. Finally, we are at the 20-foot decompression stop with our oxygen tanks, the last and longest stop. Vitya examines his shots through the tiny window of his Subal housing; he can’t wait to upload the images to his computer. I spend the time recollecting the frigate, trying to figure out what had made me so excited.

As a child, I imagined myself a noble pirate, like Errol Flynn’s Capt. Blood. I learned the names of masts and sails, and inspected pictures of sailboats. Even in my most vivid dreams, I knew it was just imagination, but I painfully wanted to see these pictures come to life. At 35, I had forgotten all of this, but hanging on my decompression stop, I suddenly realize that on this day, at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, my childish dream came true.

Viktor LyagushkinArtifacts from Oleg and a nearby wreck can help identify a shipwreck.

Under Oleg’s Spell

The next day, the weather changes again. We can work on some shipwrecks near Hogland, but not Oleg. Igor and Roman begin to vehemently argue how to take the buoy off the frigate if we cannot return to Oleg on this expedition. Smiling, Capt. Sinitsyn comes down from his cabin and settles the dispute. The coast guard has just shot the buoy, mistaking it for an automated enemy scout.

Perhaps it’s a sign — our expedition does not return to Oleg. The Baltic Sea graciously allows us to work on other shipwrecks, and they are interesting. The dives are different, and sometimes dangerous. On the Danish schooner Louise, Roman becomes entangled in nets on ascent; luckily, Igor is there to free him. On the German smuggler Archangel Gabriel, which sank in 1724, Igor finds barrels of wheat and candle tallow. Vitya and I are almost lost on the “Swede,” a nameless victim of the 1790 Battle of Vyborg. But we find no treasures. (Roman and Igor admit they have only once found wine bottles in 10 years of dives, a bottle of Moët & Chandon champagne in the admiral’s cabin of the battleship Gangut. The champagne was sweet — the Russian Royal Household preferred sweet wines at the time. By the end of the story, I am wildly envious, although I prefer brandy.)

On the last night of the expedition, I have a dream. Emperor Alexander II stands on the deck of the RC-311 and inspects a parade of the Baltic Fleet. I look for Oleg and suddenly see it incredibly close — under full sail, beautiful and majestic. Without reducing its speed, the frigate suddenly starts to submerge like a submarine. I find myself on the deck of the frigate, underwater. Fish swim around gentlemen and ladies dancing on the deck, laughing and drinking Moët & Chandon straight from bottles, saying: “How sweet it is!” I feel a painful impulse to drink, then suddenly Igor appears, shouting: “Grain and tallow in the hold got wet!” Everyone rushes to move the bags and barrels near a bronze cannon, on which Vitya sits and laughs. He gives me a bottle of champagne and says conspiratorially: “So do you understand why the czar should be referred to as Vladimir Vladimirovich? Because the czar is our president!” The cannon under Vitya suddenly turns into a huge buoy and loudly explodes, and I wake up in terror, heart pounding.

Vitya is lying in bed, impassively smoking. On the stairs to our cabin are men in uniform. They fastidiously look around at Vitya’s batteries and scattered things, then turn to Vitya: “How long have you been here?” “Fifty-two days,” Vitya says calmly, pointing to the marks over his bed. The border guards begin to depart, and one trips on a tank. The cylinder valve hisses wickedly. “What is that?” he asks.

“Oxygen tanks. Never mind, the valve is broken; it releases gas a little.”

The guards look at the light of Vitya’s cigarette, turn pale and hastily retreat. I get up and close the hissing valve — it’s a helium tank — and note to myself that smoking in bed is sometimes good.

Viktor LyagushkinArchaeologists Roman Prokhorov and Igor Galaida’s son Ivan map the Russian Imperial navy transport America, sunk in 1856 near Hogland Island. The expedition spent time on America on stormy days when it was not possible to access Oleg.

Epilogue

My dream proves prophetic in a sense. I was not particularly surprised to hear on TV some months later that Russian President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, a diver, plunged from the submarine C-Explorer-5 into the Baltic Sea to the frigate Oleg, “flagship of Czar Alexander II and the largest wooden ship at the bottom of the Baltic.”

“According to the president,” the report says, “on the submersion he walked around the shipwreck and saw the name on the stern of the ship and her cannon ports. He said that the ship was ‘in surprisingly good condition. It is very easy to read the ship’s name. Her preservation is very good.’ The president stressed that the dive was not scary, but on the contrary, very interesting. Asked if he was going to look for treasure, the president said: ‘It is not for me; let journalists do that.’ ”

Viktor LyagushkinGunners' tools were among the artifacts recovered from the Oleg shipwreck.

Viktor LyagushkinCapt. Sinitsyn looks out from the wheelhouse of the in the RC-311 during the exploration of Oleg.